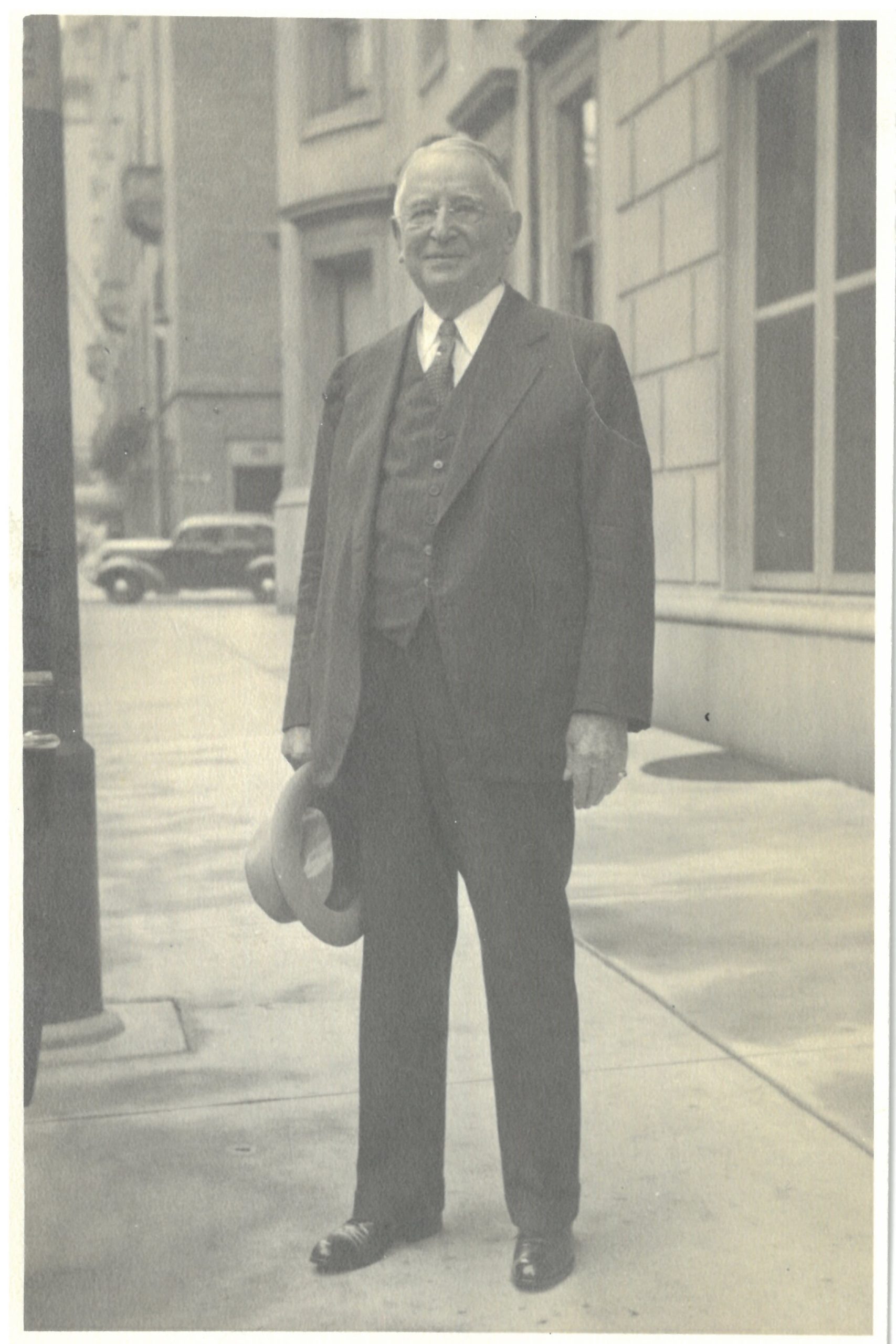

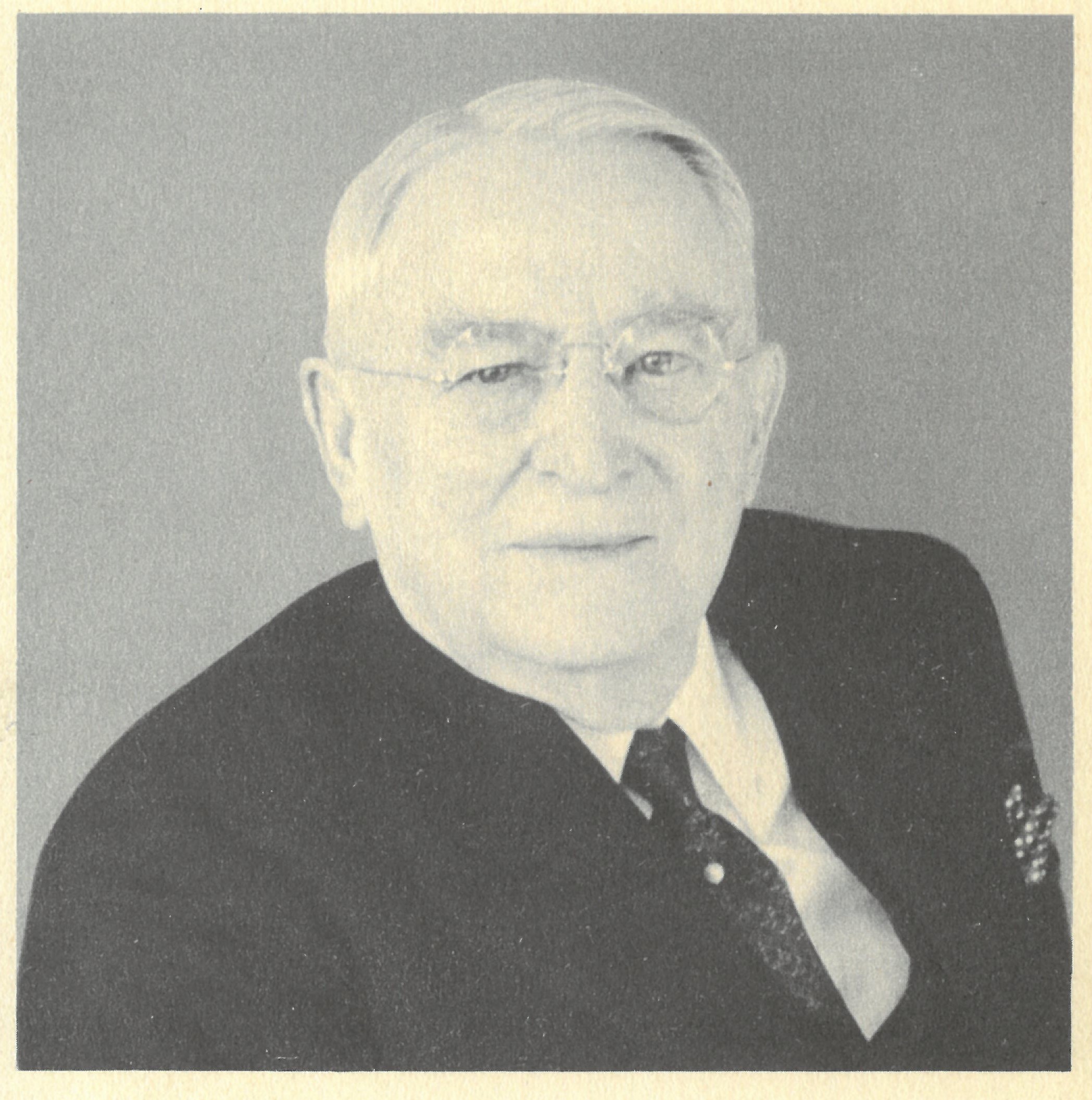

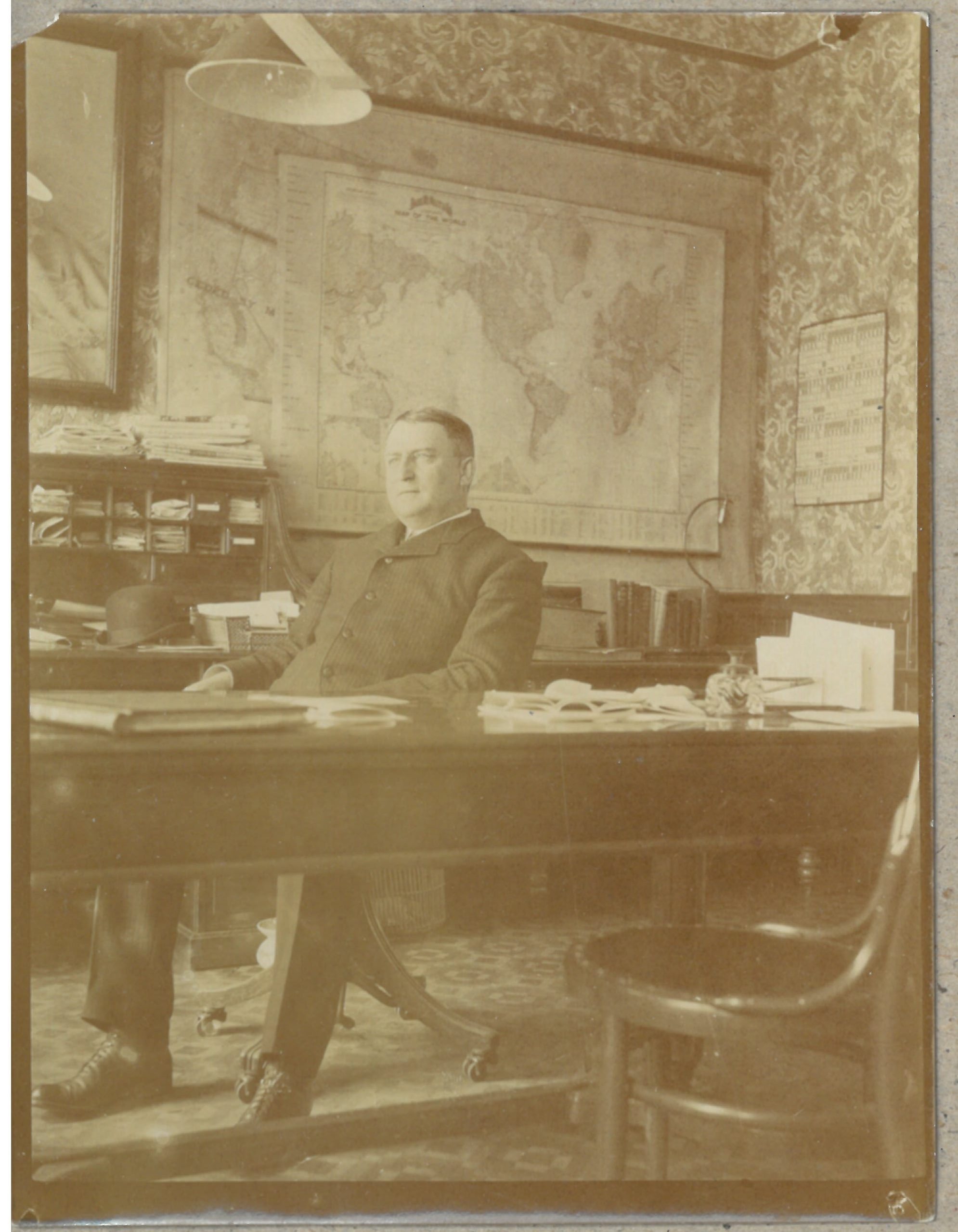

As we transition from articles about the MacDonell House to titans of industry, our obvious first article is on J.W. Van Dyke. Although he was not born in Allen County, Van Dyke’s work with the Standard Oil Company in Lima is one of the key moments in this area’s industrial history. We will start by highlighting Van Dyke’s youth and what brought him to the oil industry. Next, focusing on his time at the Lima Refinery and how he started it and ran it for sixteen years. Then, we will go over some of the highlights of his life, from industry-changing inventions to what we remember about him today. J. W. Van Dyke made the oil industry his life and changed it with careful planning and inventions in a way that few businessmen rival.

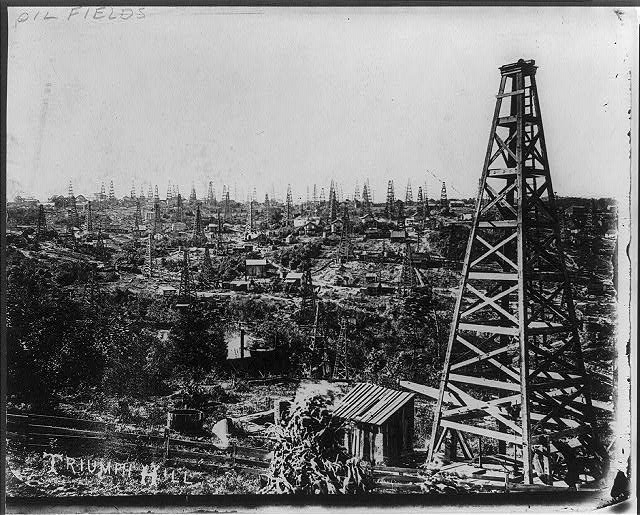

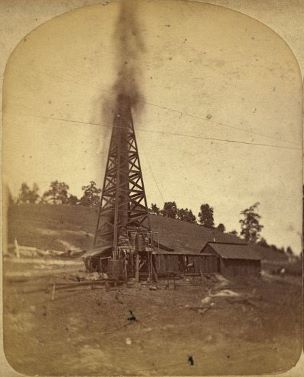

John Wesley Van Dyke was born December 27, 1849, in Mercerburg, Pennsylvania.[1]His Dutch grandfather had moved to the area and started a prosperous farm.[2] Van Dyke’s father would grow the farm to include a drover business, which is herding animals for their owners.[3] His father would die serving in the Civil War in 1861.[4] At that time, Van Dyke was left with $2,000 from his father to be collected on his twenty-first birthday.[5] Van Dyke’s education was at first typical to any child living in Pennsylvania at that time. However, his family had dreams of him following in his uncle’s footsteps as a lawyer.[6] Thus, he was sent to Tuscarora Academy, the first secondary school in Juanita County and a boarding school for only boys.[7] Van Dyke finished his studies in 1865. His grandfather and mother were still set on him going to law school, but, in 1867, Van Dyke ran away from home with his cousin, Charles Patterson because he wanted different things for his life.[8] The oil fields of Pennsylvania were the way to make money. Van Dyke started as a clerk at a store in the oil region of Venango County, then he started in the actual oil business.[9] On former Virginia Governor, H. A. Wise’s land, Van Dyke started as a pumper, then a tool dresser, and finally a driller.[10] As he learned the business and became known as a levelheaded young man who understood the oil industry. A few years later, Van Dyke suggested the purchase of a tract of land to Wise, who declined the purchase.[11] This was still before Van Dyke turned twenty-one years old, so he borrowed $1,000 from his mother and bought the land himself.[12] He sold it only a few months later for a solid profit.[13]

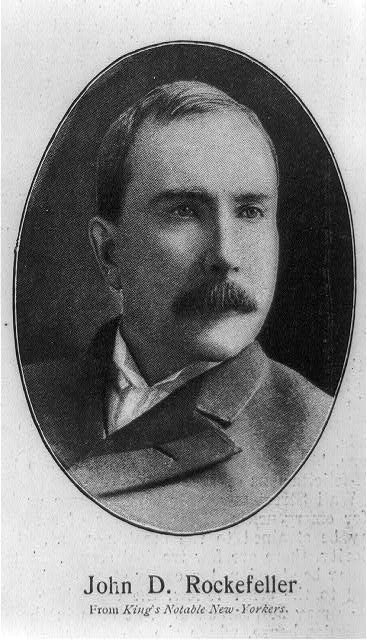

Van Dyke’s life is filled with moments where one could say “he was in the right place at the right time.” This is seen in his friendship with John Hill, who he met at a hotel frequented by oil businessmen.[14] Hill and Van Dyke hit it off instantly. A few months later Hill was promoted by the Standard Oil Company, to be henceforth called Standard, as the new manager of the Long Island Refinery.[15] Hill then brought Van Dyke to New York with him.[16] Only a couple years later, Van Dyke also rose in prestige within Standard, becoming the manager of the Standard Plant in Brooklyn.[17] In that position Van Dyke started showing how his innovations and running a tight ship brought higher efficiency to the refinery.[18] It was at that time that he would catch the eye of Standards’s CEO John D. Rockefeller.[19] They would become trusted associates and even close friends—a relationship that brought Van Dyke to Allen County.

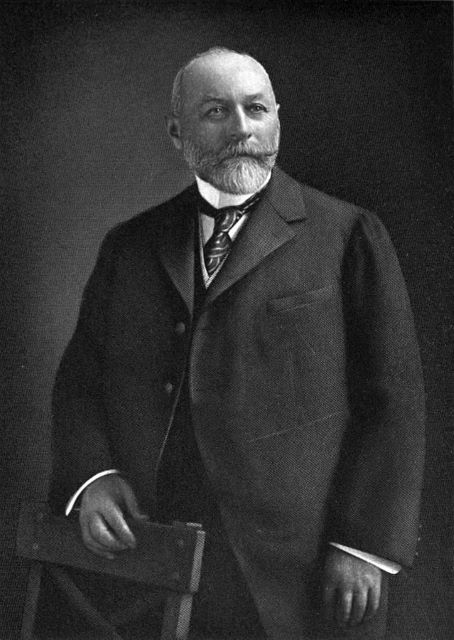

A different type of oil had been found in Ohio and Indiana; there was a lot of it, but it contained significant sulfur compounds. Standard jumped on the opportunity to set up a refinery in Allen County, even though they had yet to find a way to desulfurize the crude.[20] An astute businessman to his core, Rockefeller wanted a dream team to figure out this problem. Thus, he sent Van Dyke to Lima in 1886 and paired him with German and Canadian chemist Herman Frasch.[21] The chemist, Frasch, had already been working on a way to desulfurize oil, looking at it as a chemist. Van Dyke’s part in the puzzle was to translate Frasch’s ideas into the real world to make the methods commercially viable.[22] Frasch figured out how to separate the compounds, and Van Dyke created a “hollow water-cooled drive shaft” to be put into the furnace to recover the copper oxide that was needed to remove sulfur from crude oil.[23] With these two coinciding inventions, the Lima refinery was finally able to start a large-scale operation in 1887.[24] Not long after, the Cleveland plant used the same inventions to get it up running.[25] This is just the beginning of Van Dyke’s ability to create industry-changing inventions.

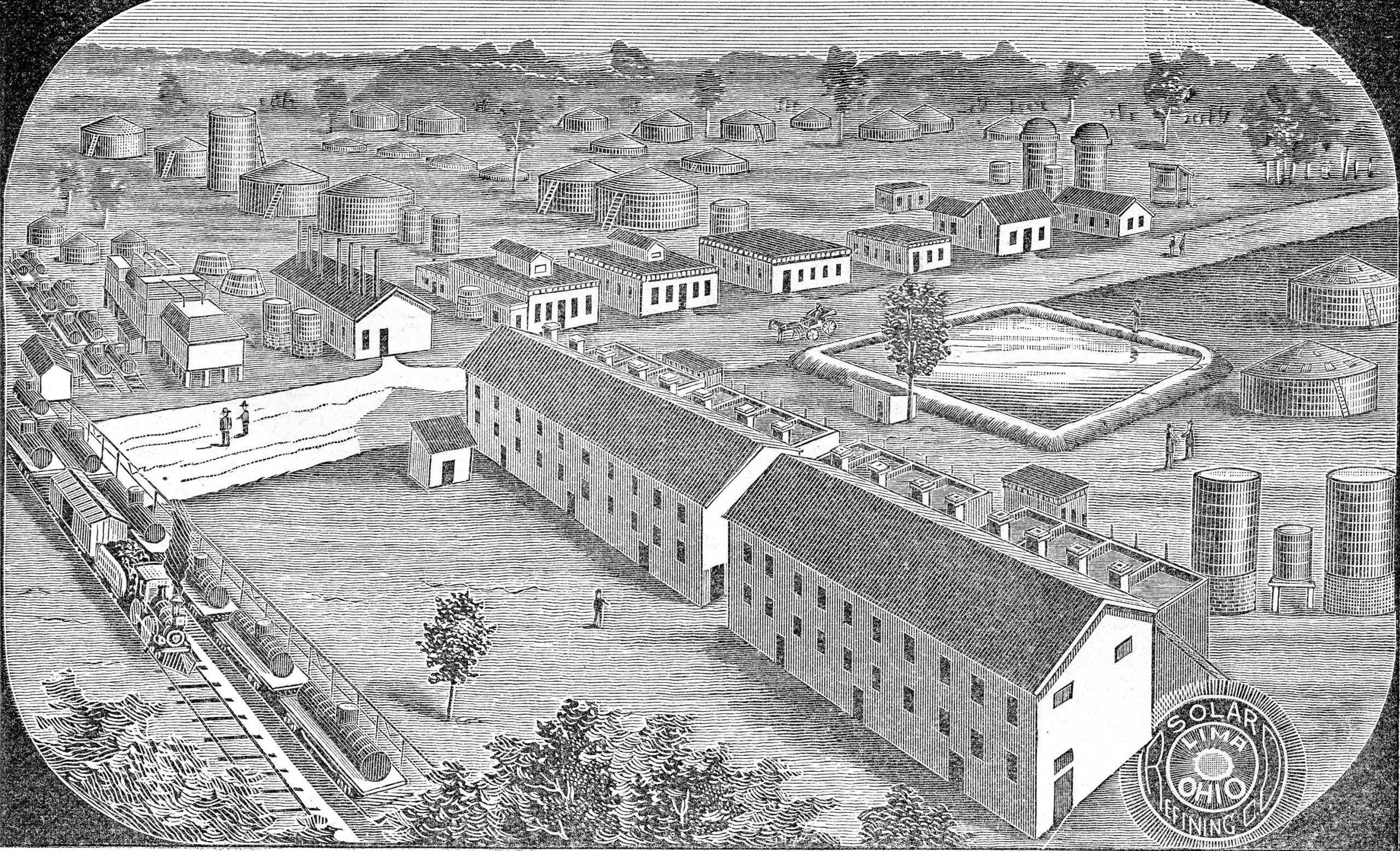

The Lima Refinery was an impressive institution. It was located on 276 acres, that were on the routes of three different rail lines.[26] Because of Van Dyke and Frasch’s inventions and its place under the Standard umbrella of refineries, it had the most modern machinery of the time.[27] It was made up of thirty brick buildings and employed around 600 people.[28] It was also stated in a newspaper article on the plant that “strikes have been unknown, and the large force has worked together happily and with good results.”[29] This was noted as being under the leadership of Van Dyke. Likewise, ahead of the times, the refinery not only produced oil and all grades of illuminating oils, but they manufactured by-products such as paraffine wax and mechanical oils.[30] That was common in Van Dyke’s refineries, selling both the oil and its by-products. The Cenovus Refinery in Lima still sells certain by-products of the oil created there. Mechanical shops were also a part of the Lima Refinery at the time; we’ll talk in the next paragraph about the inventions of Van Dyke that helped these shops. That is all to say, the Lima Refinery was as important to the areas then as it is today. According to The History of Allen County and its Representative Citizens, oil was being piped to Lima from every field in Ohio and Indiana in 1906.[31] That might be an exaggeration, but plenty of oil was flowing into the Lima Refinery because of its connections to Standard and the innovative leadership headed by Van Dyke.

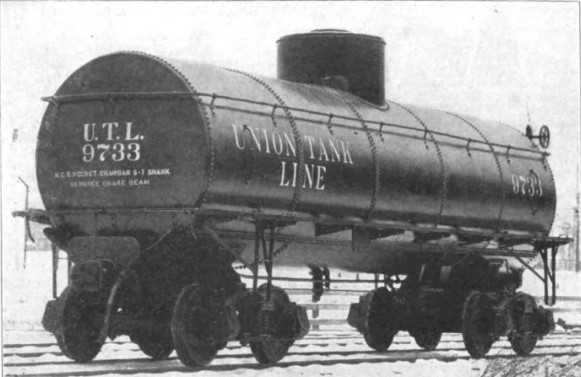

During his time at the Lima Refinery, Van Dyke worked on innovations for Standard. Most of these were engineering problems that were affecting the company as a whole. The first solution was in tandem with Frasch once again. The big problem with drilling oil in Ohio and Indiana was the limestone layer from which the oil was drilled. It decreased the oil yields causing oil wells to be drilled closer together.[32] Van Dyke and Frasch experimented and finally found a process to increase yields. They would inject oil wells with “under pressure hydrochloric acid,” which would cause the limestone to dissolve, creating more area for oil to flow toward the oil well’s shaft.[33] When The Democratic Standard of Coshocton, Ohio, described the invention they stated, “Wells doing three and four barrels, have been increased 300 to 400 percent after having been shot with glycerine and not materially increased.”[34] Because of this increase it meant thousands of dollars to the oil industry in Ohio and Indiana, which of course directly improved the Lima refinery.[35] Frasch and Van Dyke took out a patent for this way of shooting wells.[36] Another project Van Dyke contributed to while in Lima was the design of Standard’s Chicago Oil Refinery. It was, at the time, the largest refinery in the world, and Van Dyke’s knowledge helped make it productive and profitable.[37] Similarly, Standard was becoming worried about train tank cars that transported oil. The explosive nature of train accidents with tank cars was making the entire oil world fearful that the United States government would outlaw this mode of transportation.[38] So, Van Dyke put his mind to it, building a steel car with the help of the Lima Refinery mechanic shops.[39] His first design did not have a frame or a center still. Although it was tested and approved by the Railroad Master Car Builders’ Association, it was too radically different.[40] A year later, Van Dyke redesigned the tank car with a center still to make it more conventional.[41] This one was also tested by the Railroad Master Car Builders’ Association. In collision tests, the design kept the tank from moving longitudinally. Thus, causing very little to be damaged to the tank car and almost eliminating explosions.[42] Thousands of these Van Dyke tank cars were made for at least the next ten years.[43] As you can see by these examples, Van Dyke was involved in more than just running the Lima plant.

What was Van Dyke doing in Lima beyond the refinery? We know some of what Van Dyke did in his free time from Emma’s article. They threw big parties and expanded 632 W. Market St., which we can still visit today. He was also making many friends, notably Mr. A. T. MacDonell and Mrs. Elizabeth MacDonell (we will come back to that friendship near the end of this article.)[44] The unique thing about Van Dyke is that he seems almost limitlessly involved in business wherever he resides. In 1898, he was appointed to be one of the directors of the Lima Locomotive and Machine Company.[45] Both Van Dyke and Emma were voted to be trustees of the Lima Hospital Society while money was being raised to start the hospital.[46] He bought land to be developed on N. Main Street in Lima, described as being across from the Bell Block and between Metheany and Thompson blocks.[47] It was said he was going to build a five-story building there and had paid $23,000 for the land.[48] In 1901, in a group with J. D. S. Neely, H. L. Brice, and John Kerr, Van Dyke bought an electric rail line in Richmond, Indiana.[49] They bought the line for $500,000; Van Dyke was appointed as the Vice President of the group.[50] This was similar to the Lima Electric Railway Company of the time.[51] Van Dyke would also get back into the private oil drilling world with John Kerr.[52] This enterprise would turn out a bit messy because of a mistake made by Kerr’s bookkeeper. When Kerr sold the land, owning five-sixths of the land, his bookkeeper miscalculated what was owed Van Dyke.[53] Kerr sent that money only to learn shortly thereafter that it had been miscalculated; he then went and sued Van Dyke for the difference in the money.[54] There was no court case to be found, so Van Dyke might have repaid Kerr not long after or they came to some agreement keeping it out of the press.[55] All in all, we can see from these examples that even beyond the refinery, Van Dyke was busy in Lima especially in the business world.

Even though Van Dyke was growing roots in the Lima community, by 1903 Standard wanted him closer to their headquarters in New York. The Lima newspaper that first wrote about Van Dyke’s transfer stated that he had been going to New York once or twice a month to consult for the company.[56] His new position on Standard’s manufacturing committee, which met twice a week in New York, increased his time in the city.[57] This committee oversaw all the company’s properties that refined the crude.[58] Even with this promotion, Van Dyke seemed sad to leave. The news article stated, “In speaking of his removal, Mr. Van Dyke said he did not like to leave Lima and his friends. He had hoped to make his permanent home here, but of course felt he should accept a promotion.”[59] Van Dyke and Emma had made their home in Lima for around sixteen years at this point and had connected with the community. In the end, they moved to Point Breeze, New Jersey, in 1903.[60]

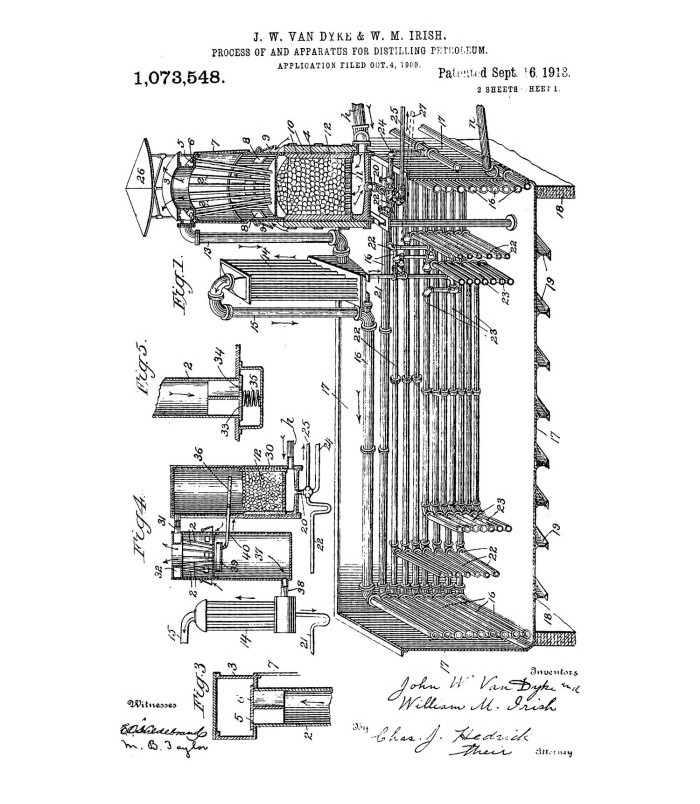

While 1903 was the end of Van Dyke’s industrial business in Lima, he went on to do many revolutionary things in the oil industry that are worth noting here. William Irish was one of Van Dyke’s associates from Allen County that Van Dyke brought to Point Breeze with him.[61] Together, they worked towards creating a better way of separating all the different chemical molecules in crude to get purer outputs. The best simplification for their “tower still” is as follows, “[It] offered greater control over condensation during refining. This technique was considered the industry’s first complete distillation process, saving millions of dollars annually in refining costs.”[62] Another invention that Van Dyke contributed to, that ended up completely changing the oil industry.

Life for Van Dyke would change drastically in 1911 when the United States Federal Courts ordered the dissolution of Standard.[63] It held too great a monopoly on the oil industry, and the company was separated into smaller pieces. This is when the Atlantic Refining Company, referred to as Atlantic here out, was created. The Atlantic’s start was rough. Its holdings were as follows: four refining properties, domestic marketing in Delaware and Pennsylvania, no oil production, no pipelines, no tankers, sixty percent of its business was foreign, yet it had no foreign sales force, no capital, nine million dollars in debt, and all of the major stockholders were also major stockholders for other Standard companies.[64] It is unsurprising that all of its officers and directors of the company shortly resigned, and all of a sudden Van Dyke was appointed as the president of Atlantic.[65] Van Dyke had one major thing going for him—his innovative creative process with Irish. That along with his levelheaded nature got Atlantic through its first years. Another thing that eventually helped Atlantic out significantly was World War I. The U.S. Air Force needed aviation-grade gasoline, and Atlantic’s Point Breeze Refinery was able to create about fifty percent of the aviation fuel sent abroad at that time.[66] It was stated that every gallon of aviation fuel cost the Army around fifty cents,[67] or around $9.45 today.[68] Understandably, that made Atlantic a lot of capital. This was undoubtably helped by Van Dyke’s position on the Petroleum Company of the Advisory Commission of the Council of National Defense.[69] Even the U.S. government knew he was someone in the oil industry to consult with. Then after the war, when the committee transferred to the Petroleum Trade Committee, Van Dyke was also a part of the commission.[70] Through his connections and inventions, Van Dyke was able to turn Atlantic into a profitable company in under ten years despite its rough beginning.

Under the umbrella of the Atlantic, Van Dyke went on to innovate even more. Under his direction, Atlantic built the first modern service station.[71] Van Dyke found his inspiration from a gas station of sorts in St. Louis.[72] In general, people were getting gas from mechanics because .[73] the service at these gas stations was never excellent.[74] In 1915, Atlantic opened the first modern gas station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[75] The Atlantic’s biography of Van Dyke noted, “[It] revolutioniz[ed] almost overnight the method of distributing gasoline and lubricants to the motoring public.”[76] The automobile world would never be the same.

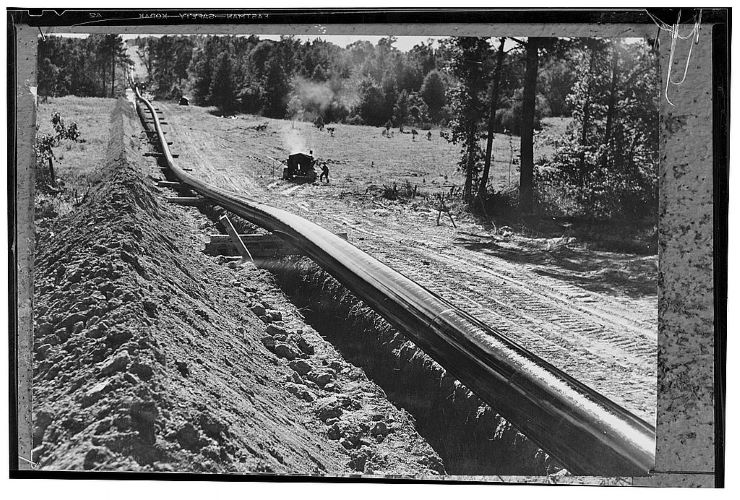

Another invention that significantly changed the oil industry was Van Dyke’s patented pipeline end protector. It was best explained as “A pressed metal cap, spot welded over the ends of the pipe at the mill and securely kept in place until the lengths of pipe are to be connected.”[77] Apparently, it could be quickly removed with a hammer when ready to place. Thus, these end metal caps would keep the inside of the pipe clean, rust-free, and ready for immediate installation in the pipeline. It was noted as being “The only method yet devised to economically and satisfactorily keep a pipeline free of harmful, foreign material and protect its joining ends.”[78] Once again, a Van Dyke invention saved the oil industry more money and was very practical.

The last thing often noted about Van Dyke’s career was his cautious business practices during the 1920s. At that time, there was such a boom in all facets of life, especially business. Van Dyke took a very unpopular stance and restrained how much the Atlantic grew during the boom of the 20s. Perhaps, like his friend Rockefeller, Van Dyke could feel the rumblings of the Great Depression, even during the easy fun of the Roaring Twenties. Therefore, when the Great Depression hit, Atlantic was able to maintain their employees’ wages, only cutting some hours, and even continued its dividends to stockholders.[79] This would be one of Van Dyke’s key legacies during his time as president of the Atlantic.

Another of Van Dyke’s legacies was his extensive donations to the Allen County Historical Society. As mentioned earlier, Van Dyke and Emma had been friends with A. T. and Elizabeth MacDonell. Elizabeth especially would often send letters to Van Dyke even years after he moved from Lima, and Van Dyke encouraged her dream of building a museum for ACHS. In 1937, he would go further than encouraging; he bought many artworks from the estate of William A. McCorkle, who had been a governor of West Virginia.[80] He immediately donated these objects to ACHS.[81] Some of the pieces are the large bronze statue of a gladiator, on display on the museum’s ground floor across from the fossil exhibition; a marble statue of Narcissus; a Chinese Shrine, on display near the Hall of Valor; and many other precious objects still a part of the museum’s collection.[82] A year later Van Dyke was also planning on donating $10,000 to the building fund for the museum, but sadly passed away before the plan came to fruition.[83] At the time of his passing, Van Dyke was declared the biggest individual contributor to ACHS by his Lima obituary.[84] Undoubtably, Van Dyke’s contributions to the ACHS are how the people of Allen County fondly remember him.

Sadly, Van Dyke became ill after a trip to Brazil in 1939.[85] He returned to his home in Philadelphia only to pass away on September 13, 1939.[86] Without many family members, Van Dyke would leave in his will an endowment of $1,500,000 for children of Atlantic workers to further their education.[87] The endowment was not to be touched for several decades, to accrue interest, causing the endowment to grow largely, making it so even in 2024 a student, whose parents worked for BP, won a scholarship from Van Dyke’s endowment.[88] During his life, Van Dyke held companies in Brazil, Spain, West and North Africa, Colombia, and Venezuela under the umbrella of the Atlantic.[89] His Lima obituary stated, “He was also a director of the Cambria & Indiana Railroad, American Shipbuilders & Shipowners, Inc., Monroe Coal Co., American Petroleum Institute, First Trust Co. of Philadelphia, First National Bank of Philadelphia, and Societe de la Maillaraye.”[90] Showing how vast J. W. Van Dyke’s interests were and what made him an industrialist with few equals.

Endnotes:

[1] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” in A Short History of The Atlantic Refining Company, 1870-1936, accessed January 8, 2025, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112052530919&seq=1, 3

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] William R. Van Dyke’s Will information, in an email “WILLIAM Van Dyke” from Bob Winder to Anna Selfridge, August 8, 2004, in J. W. Van Dyke file in the Allen County Archives.

[6] Patricia Smith, “John and Edna,” The Allen County Reporter, Vol. LX, 2005, No. 1, The Allen County Historical Society, Lima, Ohio, 6.

[7] “Tuscarora Academy Museum,” Juniata Historical Society’s website, accessed January 9, 2025, https://juniatacountyhistoricalsociety.org/museum/.

[8] Patricia Smith, “John and Edna,” The Allen County Reporter, Vol. LX, 2005, No. 1, The Allen County Historical Society, Lima, Ohio, 6.

[9] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 4.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Robert H. Colley, President of The Atlantic, The Atlantic Companies Biography of J. W. Van Dyke after his passing, September 22, 1939, in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[20] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 4.

[21] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[22] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 4.

[23] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[24] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 4.

[25] Ibid.

[26] History of Allen County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, eds. Dr. Charles C. Miller and Dr. Samuel A. Baxter, Richmond & Arnold, Chicago, Illinois, 1906, 184.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Advance,” Lima Newspaper, which is unknown, 1902 or 1903, article found in J. W. Van Dyke file in The Allen County Archives.

[30] History of Allen County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, eds. Dr. Charles C. Miller and Dr. Samuel A. Baxter, 184.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 5.

[33] Ibid.

[34] “New Device for Shooting Oil Wells,” The Democratic Standard, Coshocton, OH, October 25, 1895, ancestry.com, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7353/images/NEWS-OH-DE_ST.1895_10_25_0010.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 5.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Marian Fletcher, “The Van Dyke Collection,” Museum Mini-Talk, in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[45] “Stockholder’s Meet: And Elect Following Directors and Officers of Lima Machine Works,” Lima News, May 23, 1898, ancestry.com, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7751/images/NEWS-OH-LI_NE.1898_05_23_0003.

[46] Robert M. Reese, “Hospitals,” The 1976 History of Allen County, Ohio, John R. Carnes and Beatrice Boose Hughes eds., Unigraphic Inc. Evansville, Indiana, 1976, 487.

[47] “Deal Closed Last Night,” Lima News, January 31, 1899, ancestry.com, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7751/images/NEWS-OH-LI_NE.1899_01_31_0008.

[48] Ibid.

[49] “Lima Capital in a Mammoth Deal, Electric Road,” The Times Democrat, May 1, 1901, ancestry.com, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8207/images/NEWS-OH-TH_TI_DE.1901_05_01_0008.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] “John Kerr Sues Van Dyke Whose Home is Attached,” Republican-Gazette, October 26, 1911, article in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] “Advance,” Lima Newspaper, which is unknown, 1902 or 1903, article found in J. W. Van Dyke file in The Allen County Archives.

[57] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 6.

[58] Ibid.

[59] “Advance,” Lima Newspaper, which is unknown, 1902 or 1903, article found in J. W. Van Dyke file in The Allen County Archives.

[60] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 5.

[61] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 7.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[67] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 9.

[68] Using an the U.S. Inflation Calculator to find the same buying power $0.50 in April of 1919 would have compared to December 2024, https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

[69] “Committee of Oil Men Continued,” Warren Evening Mirror, December 31, 1917, ancestry.com, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/50294/images/NEWS-PA-WA_EV_MI.1917_12_31_0007.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Robert H. Colley, President of The Atlantic, The Atlantic Companies Biography of J. W. Van Dyke after his passing, September 22, 1939, in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[72] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 8.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Robert H. Colley, President of The Atlantic, The Atlantic Companies Biography of J. W. Van Dyke after his passing, September 22, 1939, in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[77] Wilner, Charles F., “J. W. Van Dyke: The Story of a Man and an Industry,” 10.

[78] Ibid.

[79] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[80] Marian Fletcher, “The Van Dyke Collection,” Museum Mini-Talk, in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid.

[84] “J. W. Van Dyke, 89, Succumbs in Philadelphia; Dean of Oil Industry,” Unknown Lima Newspaper, circa September 1939, article found in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[85] “John Wesley Van Dyke,” Find A Grave, accessed January 10, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/91323317/john-wesley-van_dyke.

[86] “J. W. Van Dyke Memorial Scholarship Fund Endowment,” Cal Poly, accessed January 10, 2025, https://calpoly.academicworks.com/opportunities/19506.

[87] “$1,500,000 Left to Aid Children,” Philadelphia Record, September 17, 1939, article in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

[88] “J. W. Van Dyke Memorial Scholarship Fund Endowment,” Cal Poly, accessed January 10, 2025, https://calpoly.academicworks.com/opportunities/19506.

[89] “J. W. Van Dyke, 89, Oil Field Pioneer,” The New York Times, September 1939, copy of article in J. W. Van Dyke file at the Allen County Archives.

[90] “J. W. Van Dyke, 89, Succumbs in Philadelphia; Dean of Oil Industry,” Unknown Lima Newspaper, circa September 1939, article found in J. W. Van Dyke File at the Allen County Archives.

Image Credit:

[Pilot standing in front of U.S. Army airplane during World War I], c. 1918, LC-USZ62-99040, accessed January 29, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90706901/.

[Trademark registration by The Atlantic Refining Company for Atlantic Refining Company brand Petroleum], September 16, 1873, LC-DIG-trmk-1t01460, accessed January 29, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2020745675/.

America’s petroleum industries pour out fuel and lubricants for the United Nations. Over hills and mountains, across broad rivers and through densely weeded regious runs what the U.S. calls the “Big Inch,” the largest oil pipeline in the world, built specially to expedite supplies of oil derivatives to U.S. armed forces and the armies of the United Nations. The pipe line extends from the oil fields of the U.S. southwest state of Texas to the New York City – Philadelphia oil district of the U.S. eastern Atlantic coast, a distance of almost 1,400 miles (2240 kilometers). It is 24 inches in diameter and delivers a daily flow of 300,000 barrels. The picture shows the pipeline in the course of building. A section, before being lowered into the trench built to receive it, has been coated with hot asphalt paint. The completed pipeline cost $95,000,000, c. 1944, LC-USW4- 029615, accessed January 29, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017877183/.

Atlantic Refinery, Point Breeze, 1939, image courtesy of the Dallin Aerial Surveys Collection, Hagley Library and Museum.

Atlantic Refining Co. Filling Station, 1921, Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, 1901-2000, accessed January 29, 2025, https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt:715.2182.CP.

Engraved Portrait of United States Chemist Herman Frasch, 1918, The Cyclopaedia of American Biography, accessed January 29, 2025, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CAB_Frasch_Herman.jpg.

Frank Robbins, Lady Hunter well, flowing 100 feet high, ca. 1880, LC-DIG-stereo-1s01744, accessed January 28, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008678994/.

John Davison Rockefeller, 1839-1937, 1901, LC-USZ62-78346, accessed January 28, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002706139/.

Process and Apparatus for Distilling Petroleum, September 16, 1913, accessed January 29, 2025, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth853834/.

The Van Dyke Tank Car—Capacity 10,000 Gallons, in Railroad Gazette, Vol. 35, No. 10, 1903, accessed January 28, 2025, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015013053841&view=1up&seq=190&q1=van+dyke/.

Triumph Hill [Tidioute, PA], c. 1907, LC-USZ62-70583, accessed January 28, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003654756/.

All other images are from the Allen County Archives or were taken by the Allen County Museum staff.

Leave A Comment