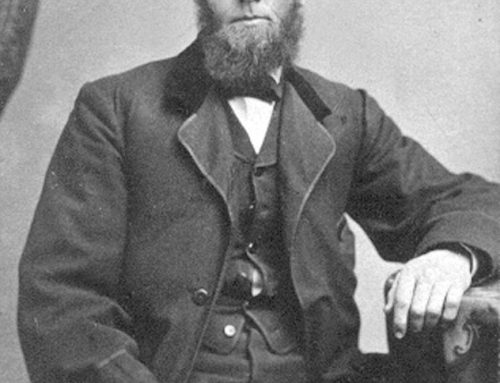

“Calvin S. Brice; a determined man, an aggressive man… He was a veritable steam engine.”[1]

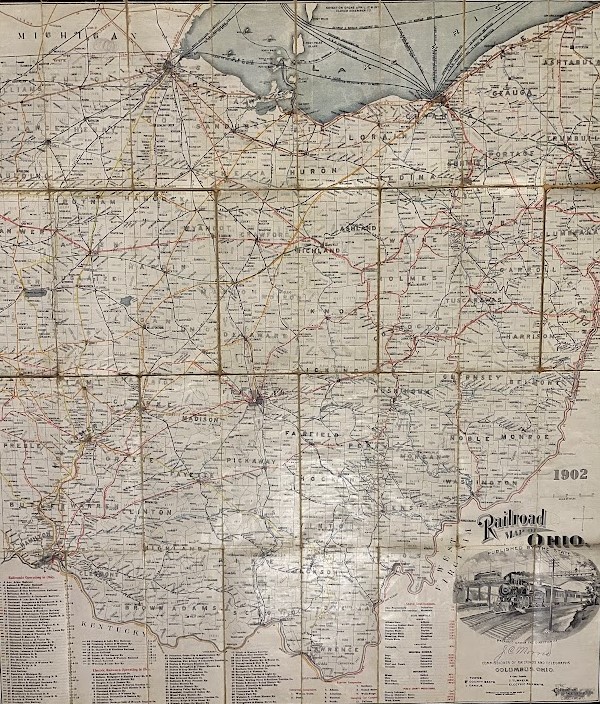

Recounted the Lima News in one of Brice’s numerous obituaries. Calvin Brice is one of the men of Allen County who did so much in his lifetime that this author has to write two articles to cover his impact on Lima and Allen County. This article will focus on his early life and his foremost career, railroads. The late 1800s and early 1900s was an era of gambling on railroad lines. If you had enough money to be a stockholder or build a line yourself, there was a chance of great rewards but just as often significant losses. Many people during this time became multi-millionaires while others lost it all. Brice was among the number of businessmen who lost significant funds in the railroad gamble. He was often praised for his speculative abilities regarding train lines.[2] Still, it was often noted that even Brice lost money in this industry.[3] This gambling spirit and utter determination was the hallmark of Calvin Brice’s life-long career in the railroad industry.

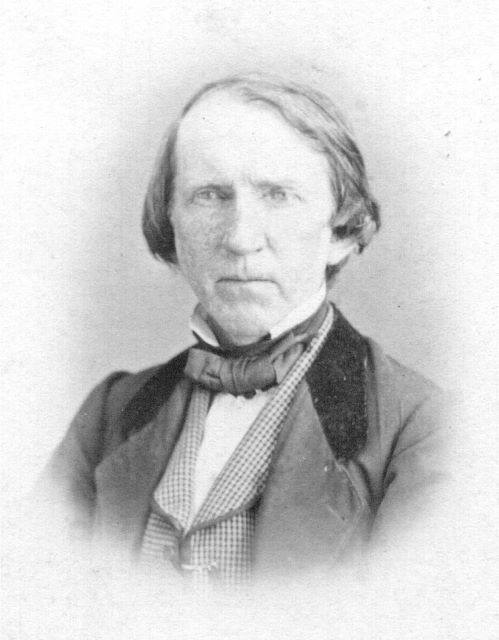

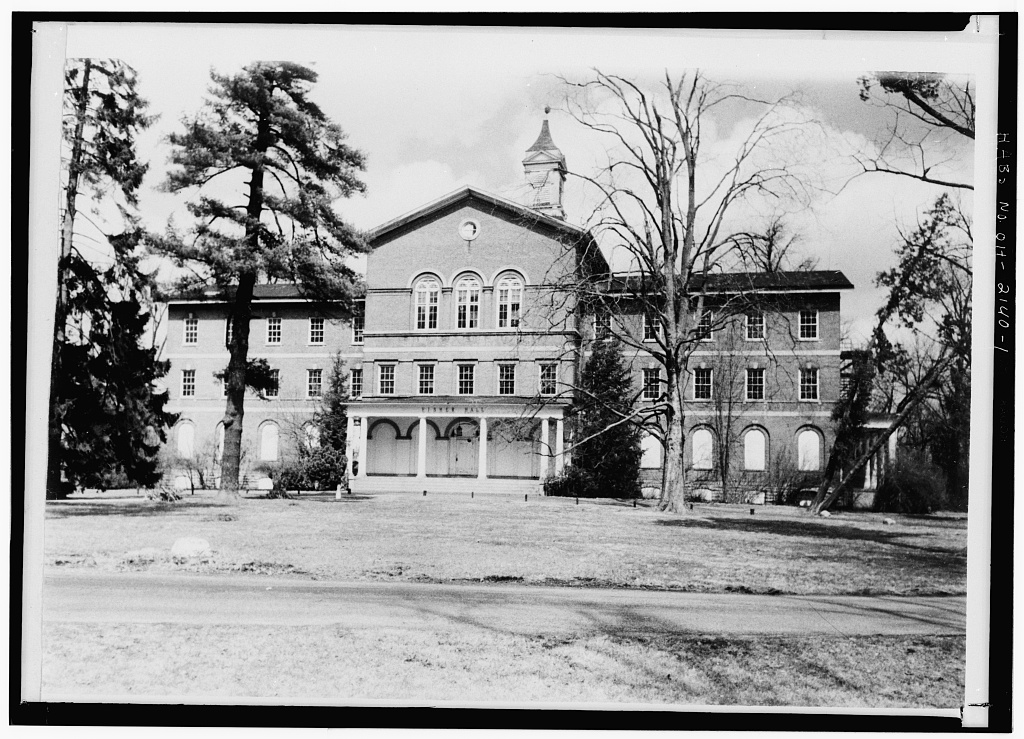

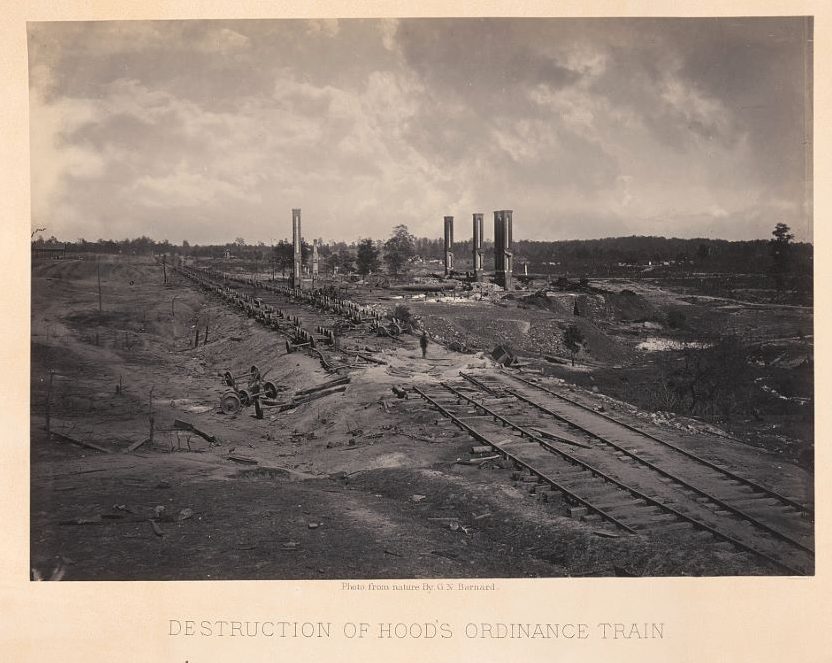

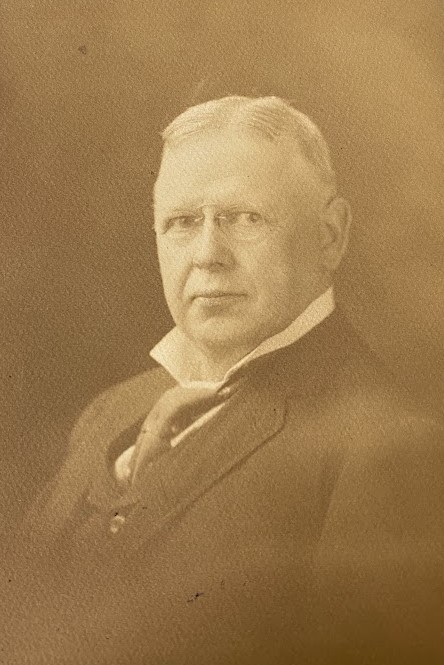

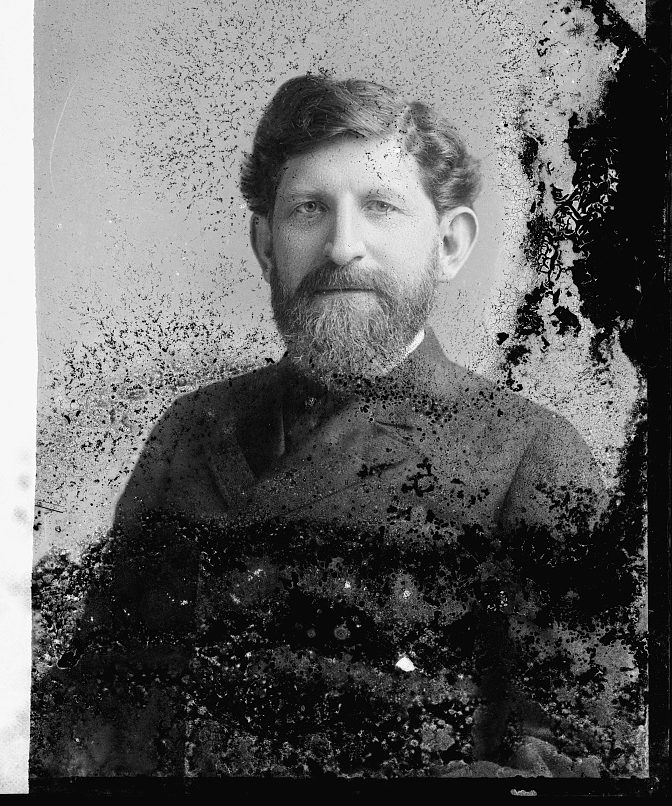

Calvin Stewart Brice was born September 17, 1845, to William and Elizabeth Brice in Morrow County, Ohio.[4] William was a Presbyterian minister, and the family was at most times relatively poor.[5] However, even with a lack of funds, Brice’s education was a priority. Thus in 1859, at the age of thirteen, he was enrolled in a college preparation program at Miami University.[6] A year later, he was placed in the university’s freshman class.[7] When the Civil War began the following year, Brice tried to join the war with fellow Miami University students.[8] However, he was only fifteen and was sent back to the university.[9] Then, in April 1862, he reenlisted again under Professor R. W. McFarland’s Company A., 86th O.V.I.[10] This was a three-month term of servicespent in West Virginia guarding the union’s railroads.[11] This no doubt taught Brice the vital nature of rail lines in the 1800s for the transport of goods and people. After Brice’s three-month service was completed, he went back to Miami University to resume his studies,[12] graduating the following June from Miami University.[13] Brice taught in the Lima public school system for a term before changing positions and becoming a clerk at the Allen County Auditor’s Office.[14]

In 1864, Brice reenlisted in the Union Army once more.[15] The difference this time was that Brice recruited a company of his own and was commissioned as the captain of Company E, 180th O.V.I.[16] This represents for the first time the persuasiveness of Brice; he recruited a whole company in the third year of the Civil War. His company spent their service until the war’s end guarding and rebuilding rail lines in Tennessee and North Carolina.[17] Another reinforcement for Brice of the importance of railroads. When the Civil War ended in May 1865, Brice was appointed lieutenant colonel for his commendable service, but the army did not muster him.[18] Brice ended his five years of study and the war without a definitive path.

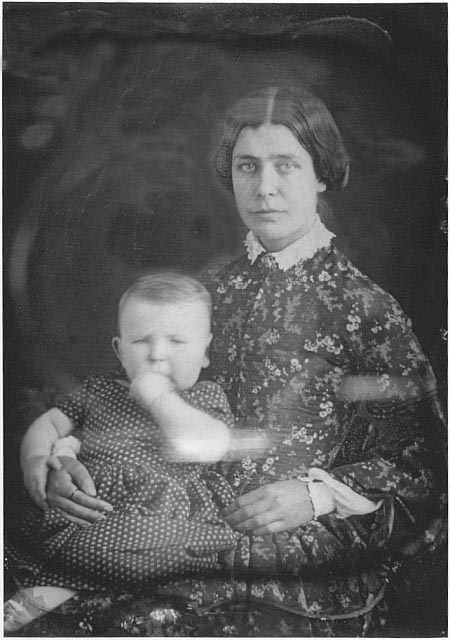

If you have no plan and you are good at persuading others, why not go to law school? That’s what Brice chose. In the fall of 1865, Brice entered law school at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor.[19] The following year he passed the bar and was able to practice law in the United State’s courts.[20] Only a year later, in 1867, Brice was appointed as the North District of Ohio’s Commissioner of the Circuit Court.[21] Brice would begin his decade-long partnership with James Irvine in 1868,[22] holding offices in Lima, as the Irvine & Brice Firm.[23] Oral history tells us that Irvine was a Republican and Brice a Democrat because they wanted to have clients from both political parties.[24] After Brice was finally settled into a career, he married Catherine Olivia “Liv” Meily on September 7, 1869.[25] Liv’s parents were John and Catherine Meily.[26] Mr. Meily was an iron moldmaker and owned and operated the first foundry in Allen County.[27] Liv was a very intelligent woman, having graduated from Miami University’s Western Female Seminary in 1866.[28] She was a perfect wife and helpmate to Brice and his careers, known to be good at entertaining and helping promote his aims.[29] Thus, began Brice’s career in law and married life.

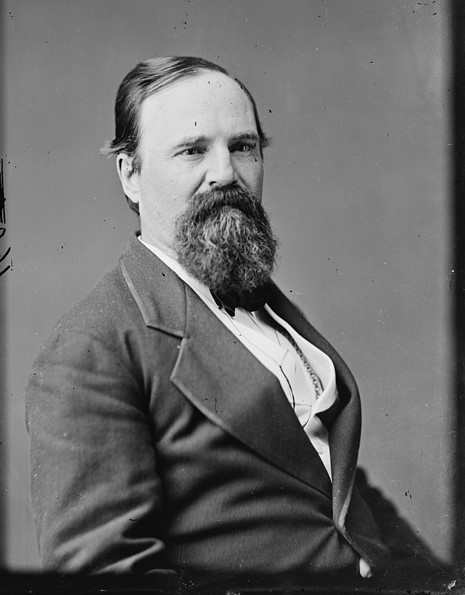

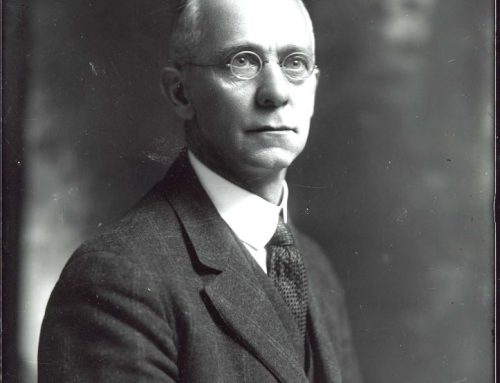

It is remarked by almost every account that being a small-city lawyer was not a prosperous era for Brice.[30] However, Brice had a quick mind and knew the laws of the land. When he noticed the Lake Erie & Louisville, L.E.&W., was running out of money when the line reached Findlay in 1871, Brice brought a recently enacted law to Charles Foster, the owner of the line. Foster was an entrepreneur himself, a man of means unlike Brice at this time.[31] Brice explained how they could use this new law to fund the L.E.&W. Foster brought the rail line directors together,[32] and the directors and Foster gave Brice the reigns to try this funding idea. In an interview after Brice’s death, Foster claimed it was only because of Brice’s knowledge of this law and his city-to-city money raising that L.E.&W. was able to be finished finally in 1878.[33] Foster was particularly proud of this because Brice did not have a name at this time to inspire people to invest; instead, he only had his persuasion skills to lean upon.[34] After this, Brice became part of the L.E.&W.’s legal department and acquired stocks in the company.[35] It was these stocks in the company and his partnership with Foster that eventually led to Brice becoming the Vice President of L.E.&W. in 1879.

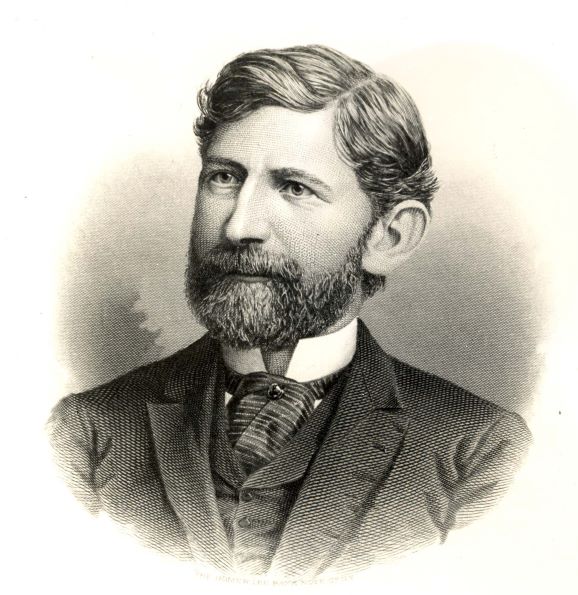

Brice’s connections to L.E.&W. and Foster firmly entrenched him in the railroad industry. Foster moved towards his political career during the completion of the L.E.&W. and spearheaded a merger with the Seney Syndicate of New York.[36] The Seney Syndicate was full of men doing the railroad gamble, not developers or builders; they were in it for the money pontentials of the industry at the time.[37] As soon as Foster introduced Brice to the head of the Seney Syndicate, George I. Seney, Brice was taken into the fold.[38] Seney was said to have stated, “He [Brice] is the most remarkable man I ever met. He gives opinions promptly. When I ask my lawyers for certain opinions it takes them months to give them. Brice gives his at once.”[39] So, when Brice had an idea about undermining railroad tycoon William Vanderbilt’sLake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, the Seney Syndicate was all ears.[40] In truth, Vanderbilt’s railroad was not utilizing this shoreline line to the extent that it should have been.[41] The Seney Syndicate began building an extension to the New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, N.Y.C.&St.L., along the same shoreline.[42] The area in question had been partially graded for a railroad back in 1859 but was never completed, and they were able to make use of some of that work when they started the project in 1880.[43] Even with the previous grading, this extension turned out to be an expensive enterprise.[44] The Seney Syndicate had over extended their original budget significantly by the end of the project in 1882.[45] Soon their only hope to get out of the red was for Vanderbilt to buy the line to and keep his monopoly in the area.[46] However, Vanderbilt was smart, and he realized that the N.Y.C.&St.L. line was going to undermine his railroad significantly. He did not necessarily wantto roll over to Brice and the Seney Syndicate. Knowing this, Brice devised another plan: to have his wealthy friend Jay Gould act as a prospective buyer of the line when Vanderbilt came to negotiate.[47] Gould owned some rail lines in the area and was actively trying to break up the Vanderbilt monopoly, so it was not a farfetched ruse.[48] Fighting with Gould to purchase the line, Vanderbilt ended up spending $1,500,000 on the rail line three days after it was completed, giving a seventy-five percent profit to the Seney Syndicate.[49] This purchase turned Brice into a railroad tycoon, and he finally had enough money to railroad gamble on a larger scale. More importantly perhaps, he finally made a name for himself as someone who understood the railroad industry as well as the gamble.

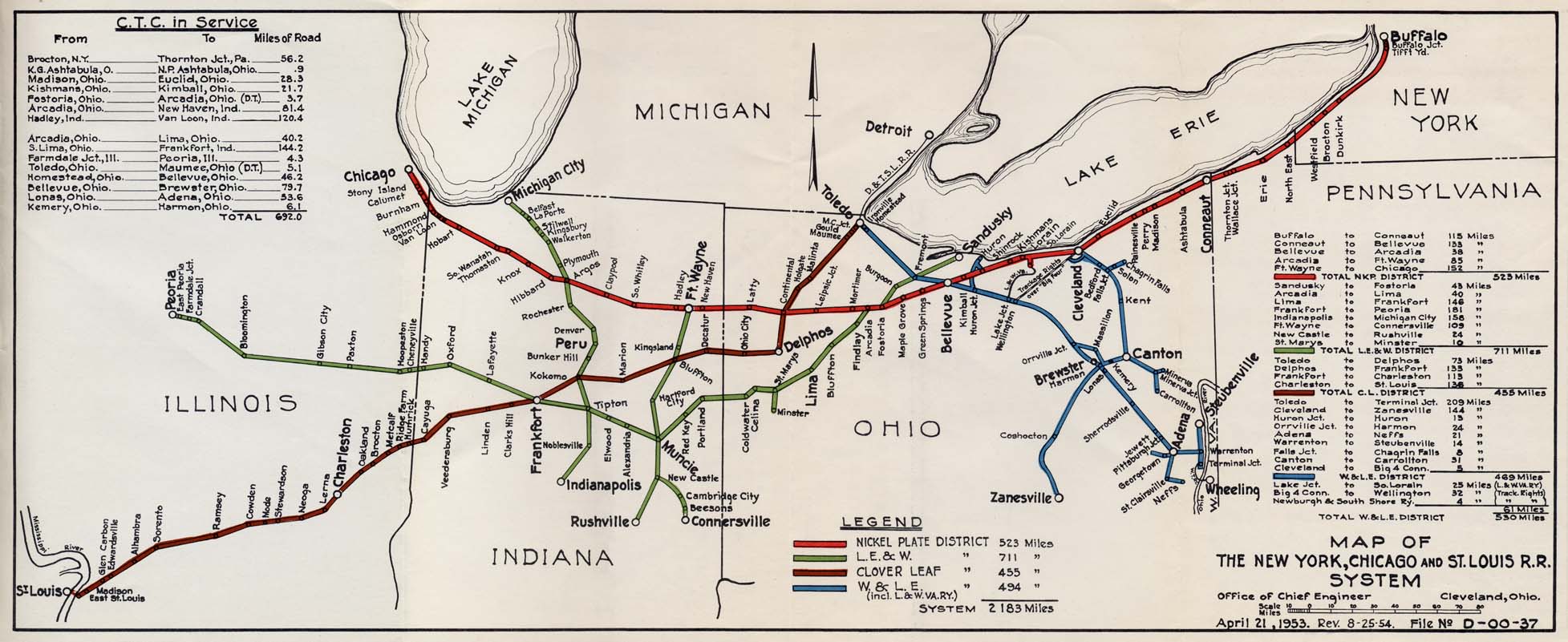

After the deal closed, the name of N.Y.C.&St.L was changed to the Nickel Plate Road, either in reference to how much Vanderbilt spent on it or because of the type of metal used in building it.[50] The Nickel Plate Road is by far one of the most impactful railroads to Allen County, and its history started with Calvin Brice.

With new prestige following Brice in the railroad industry, there was no stopping him. One thing he became primarily known for during his life was reorganizing dying railroad properties and companies to make them fiscally stable once more.[51] This was again playing the railroad gamble–some succeeded and some failed.[52] Restructuring these railroad companies also made him a director, president, or owner of many of them. To name all of them would be lengthy and probably not too interesting here, but know he was involved with around twenty-two railroad companies from the American South to the Midwest.[53] With that number growing during the 1890s, Brice had another ingenious idea: to connect all of his railroads and build a huge railroad conglomerate. The first time this research found a mention of this idea in the newspapers was in September of 1895.[54] The article is about how Brice purchased the Ohio Southern Railroad Company and found it was a missing piece for connecting some of his other train lines.[55] He kept connecting other rail companies to his main lines for the next two years, having them run from Duluth, Minnesota, to Cincinnati, Ohio.[56] A central focus of this line for Brice was connecting to harbors on the Great Lakes and eventually connecting to the Atlantic seaboard.[57]

Around July 1897, the conglomeration plan hit a significant snag as some of the railroad companies were in legal cases.[58] Therefore, the consolidation of the rail lines under one management could not come to fruition until the legal cases were finished. By the time of Brice’s death, there is no evidence that the large mainline idea from Duluth to the Atlantic seaboard was ever finished. However, in 1898, Brice found a way to connect Chicago to the Atlantic seaboard through all of his lines and only needed to build around ninety miles of track for it to be completed.[59] This was under L.E.&W., and the plans were all set, but he passed in December 1898.[60] Brice had a critical role in the railroad industry during the 1880s and 90s and almost made an enormous monopoly from the Midwest to the Northeast.

Beyond the United States, Brice planned a few rail lines for other countries. His most successful was a railroad in Jamaica built for the British Government.[61] The far more important one for Brice’s story was the proposed Hankow-Canton Railroad in China. While serving in the United States Senate, Brice met many important international people, one of them being Chinese businessman Li Hung Chang.[62] This Chinese statesman thought China should become a capitalist society like the United States and proposed to Brice a railroad project.[63] Brice was in charge of building the syndicate to invest in the proposed rail line that would conduct a thousand-mile survey for a track from Hankow to Canton.[64] Some of the men who joined the syndicate included: Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, some of the Vanderbilts, and many more influential persons.[65] Together they formed the China-American Development Company and signed a contract to start the survey on April 18, 1898.[66] Only a week later, the Spanish-American War broke out, pausing the project for seven months.[67] At the end of the war the survey team finally left for China only to find the new Chinese government was not interested in working with them.[68] The Hankow-Canton Railroad would not be completed until the 1920s by a British company.[69] The China-American Development Company did not pull out from China until a few years after Brice’s death.[70] However, Brice had tied up a significant amount of his fortune in the prospective railroad.[71] The railroad gamble did not work out for Briceas he left no property for his family and around $600,000 at the time of his death.[72] Leaving the Brices poorer than they had been since the Nickel Plate Road. However, after the China-American Development Company withdrew, some money was returned to the syndicate.[73] It is ultimately unknown how much the Brices received from this deal. In the end, Brice had an unsuccessful railroad gamble, but who knows what would have happened if he had not passed away.

Thus ends the story of Calvin Brice’s early life and railroad career. He was well educated even though he came from a lower-means household. He served three times during the Civil War and was promoted to lieutenant colonel for his meritorious service. Even though lawyering in Allen County was not his best fit, he found his niche in railroads. Brice built the Nickel Plate Railroad and improved around twenty-two other rail companies. The railroad gambling did not reward Brice in the end, but this is not the end of his story. Next month, we will talk about his career in politics, Allen County businesses, banking and insurance, and many other industries in which he dabbled. We will also learn more about the end of Brice’s life. Railroads were the heart of Calvin Brice’s fortune and career, but they helped and hindered him with the ever-present railroad gamble.

Endnotes:

[1] “Calvin S. Brice,” Lima News, December 16, 1898, accessed March 3, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7751/images/NEWS-OH-LI_NE.1898_12_16_0004.

[2] “Five Millions in Five Years,” New York Times, May 23, 1885, In Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Calvin Stewart Brice,” Find A Grave, accessed February 26, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6839795/calvin-stewart-brice.

[5] “Millionaire Calvin S. Brice Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia,” New York Journal, December 16, 1898, in Brice File in the Allen County Archives.

[6] “The World of Calvin Brice,” in Men of Old Miami, in Brice File at the Allen County Archive, 210.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Sue Clover, “Calvin Stewart Brice,” Docent Training, September 16, 1998, in Brice File at the Allen County Archives, 1.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Brice Label ACM.

[12] Sue Clover, “Calvin Stewart Brice,” Docent Training, September 16, 1998, in Brice File at the Allen County Archives, 1.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] History of Allen County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, eds. Dr. Charles C. Miller and Dr. Samuel A. Baxter, Richmond & Arnold, Chicago, Illinois, 1906, 331.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Local Matters,” The Democrat, September 11, 1967, In Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[22] “Senator Calvin Stewart Brice,” Label at the Allen County Museum.

[23] Sue Clover, “Calvin Stewart Brice,” Docent Training, September 16, 1998, in Brice File at the Allen County Archives, 1.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Two Short Years Did the Devoted Wife Survive,” The Times-Democrat, Lima, OH, December 17, 1900, in Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[26] Anna Selfridge, “Family Group Sheet,” in Brice File at the Allen County Archives

[27] “Two Short Years Did the Devoted Wife Survive,” The Times-Democrat, Lima, OH, December 17, 1900, in Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[28] Sue Clover, “Calvin Stewart Brice,” Docent Training, September 16, 1998, in Brice File at the Allen County Archives, 2.

[29] “Two Short Years Did the Devoted Wife Survive,” The Times-Democrat, Lima, OH, December 17, 1900, in Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[30] “Senator Calvin Stewart Brice,” Label at the Allen County Museum.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] “Calvin Brice Dead.” Unknown Lima Newspaper, c. December 1898

[36] “Foster,” Republican Gazette, December 1898, in Brice File at the Allen County Museum.

[37] https://www.museum.state.il.us/RiverWeb/landings/Ambot/ECON/ECON4.htm

[38] “Foster,” Republican Gazette, December 1898, in Brice File at the Allen County Museum.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “Millionaire Calvin S. Brice Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia,” New York Journal, December 16, 1898, in Brice File in the Allen County Archives.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “Millionaire Calvin S. Brice Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia,” New York Journal, December 16, 1898, in Brice File in the Allen County Archives.

[44] “Calvin Brice, The Seney Syndicate & the Nickel Plate,” Label at the Allen County Museum

[45] Ibid.

[46] “Millionaire Calvin S. Brice Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia,” New York Journal, December 16, 1898, in Brice File in the Allen County Archives.

[47] Ibid.

[48] “Jay Gould,” Britannica Money, accessed March 17, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/money/Jay-Gould.

[49] “Calvin Brice, The Seney Syndicate & the Nickel Plate,” Label at the Allen County Museum

[50] “Nickel Plate Road,” The Alphabet Route, accessed March 12, 2025, https://www.alphabetroute.com/nkp/history.php.

[51] “Millionaire Calvin S. Brice Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia,” New York Journal, December 16, 1898, in Brice File in the Allen County Archives.

[52] “Five Millions in Five Years,” New York Times, May 23, 1885, In Brice File at the Allen County Archive.

[53] “Senator Calvin Stewart Brice,” Label at the Allen County Museum.

[54] “Brice-Thomas,” Times Democrat, September 6, 1895, In Brice File at the Allen County Archives.

[55] Ibid.

[56] “C. A. & C. Directors,” The Times Democrat, March 21, 1896, accessed March 3, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8207/images/NEWS-OH-TH_TI_DE.1896_03_21_0004 and “The Brice System,” The Times Democrat, April 27, 1897, In Brice File at the Allen County Archives.

[57] “The Brice System,” The Times Democrat, April 27, 1897, In Brice File at the Allen County Archives and “Scheme,” Lima Daily News, April 21, 1898, accessed February 28, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8017/images/NEWS-OH-LI_DA_NE.1898_04_21_0005.

[58] “The Railroads,” Times Democrat, July 30, 1897, In Brice File at the Allen County Archives.

[59] “Scheme,” Lima Daily News, April 21, 1898, accessed February 28, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8017/images/NEWS-OH-LI_DA_NE.1898_04_21_0005.

[60] History of Allen County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, eds. Dr. Charles C. Miller and Dr. Samuel A. Baxter, Richmond & Arnold, Chicago, Illinois, 1906, 332.

[61] “The World of Calvin Brice,” in Men of Old Miami, in Brice File at the Allen County Archive, 222-3.

[62] Ibid., 223.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid

[69] “Canton-Hankow Railway, Britain’s Gift to China,” The Syndey Morning Herald, November 21, 1935, accessed March 13, 2025, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/17227136.

[70] Ibid.

[71] “Brice Fortune,” Lima Daily News, January 6, 1899, In Brice File at the Allen County Archives.

[72] Ibid.

[73] “Canton-Hankow Railway, Britain’s Gift to China,” The Syndey Morning Herald, November 21, 1935, accessed March 13, 2025, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/17227136.

Photo Credit:

C.M. Bell, “Hon. C.S. Brice,” [between January 1891 and January 1894], LC-DIG-bellcm-02999, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016690450/.

“1. EXTERIOR, SOUTH FRONT – Oxford Female College, Fisher Hall, Miami University Campus, Oxford, Butler County, OH,” HABS OHIO,9-OXFO,3A—1, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/oh0082.photos.129237p/.

Barnes, George N., “Destruction of Hood’s ordinance train,” 1866, LC-DIG-ppmsca-94054, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2024641481/.

“Foster, Hon. Chas of Ohio, Secty of Treasury (Harrison admn),” [between 1865 and 1880], LC-DIG-cwpbh-05004, accessed March 18, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017895260/.

All other images are from the Allen County Archives, Railroad Archives, or taken by an Allen County Museum staff member.

Leave A Comment