“[Grosjean] has by his indomitable enterprise and progressive methods contributed in a material way to the advancement of his locality, and during the course of an honorable career has met with success, being a man of energy sound judgement and honesty of purpose.” [1]

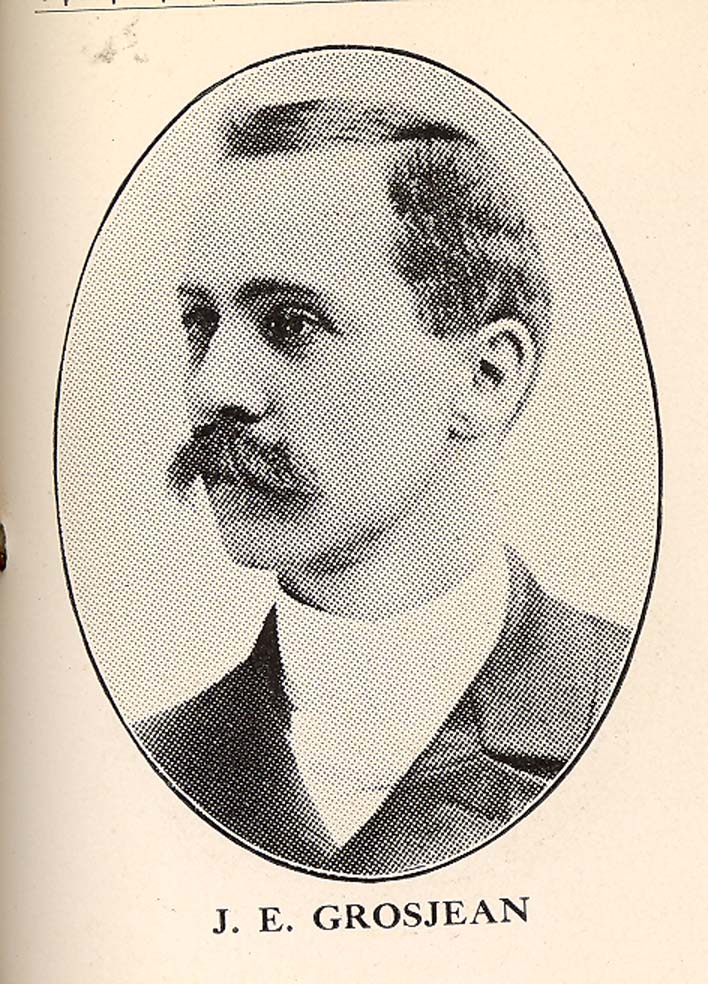

This quote was included in James E. Grosjean’s mini biography in A Standard History of Allen County, Ohio, published in 1921, more than a decade before Grosjean’s passing. J. E. Grosjean is a central figure in Allen County history due to his numerous enduring legacies. The most beloved of these legacies are his “spectacular machines,” with his Noah’s Ark being the best known. Like some of the other prominent figures in this year’s Titans of Industry series, Grosjean will need to be featured in two separate articles. The breadth and depth of what he accomplished in his life is a compelling story that deserves that much time and attention. Luckily, Grosjean often switched careers and hobbies during his life every few years. Thus, these two articles will mostly be told chronologically. This one will cover his early life, his career in undertaking, the building and display of his spectacular machines, and then his shoe store. James E. Grosjean was a man with innovation and creativity always on his mind, improving life and making something exciting were his two main aims.

James Eugene Grosjean was born on March 1, 1861, in Wayne County, Ohio.[2] His parents were Edward and Caroline Wizard Grosjean.[3] Edward was a farmer and a carpenter.[4] Grosjean did not have an extensive education. He attended common school and then did two years in a school in West Lebanon, Ohio.[5] At the age of nineteen, he started learning carpentry, specifically cabinet making, which would come in handy with many of his later careers.[6] He apprenticed and worked for two years in Mount Easton, Ohio.[7] Around 1882, Grosjean moved to Fredericksburg, Ohio, where he was both a furniture maker and an undertaker.[8] On February 18, 1886, Grosjean married Nanie Armstrong.[9] They would have two girls Pearl and Mary.[10] Sadly, Mary passed away at the age of three, not long after they moved to Lima.[11]

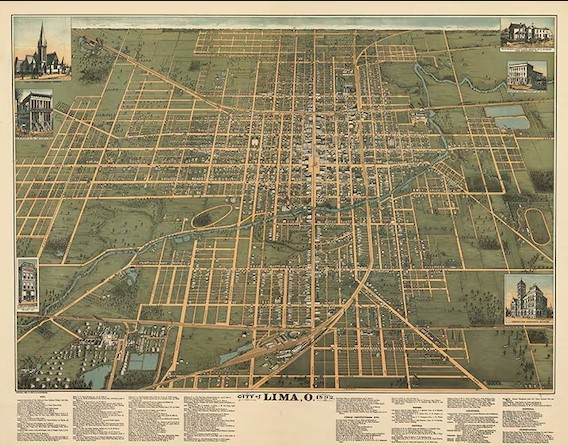

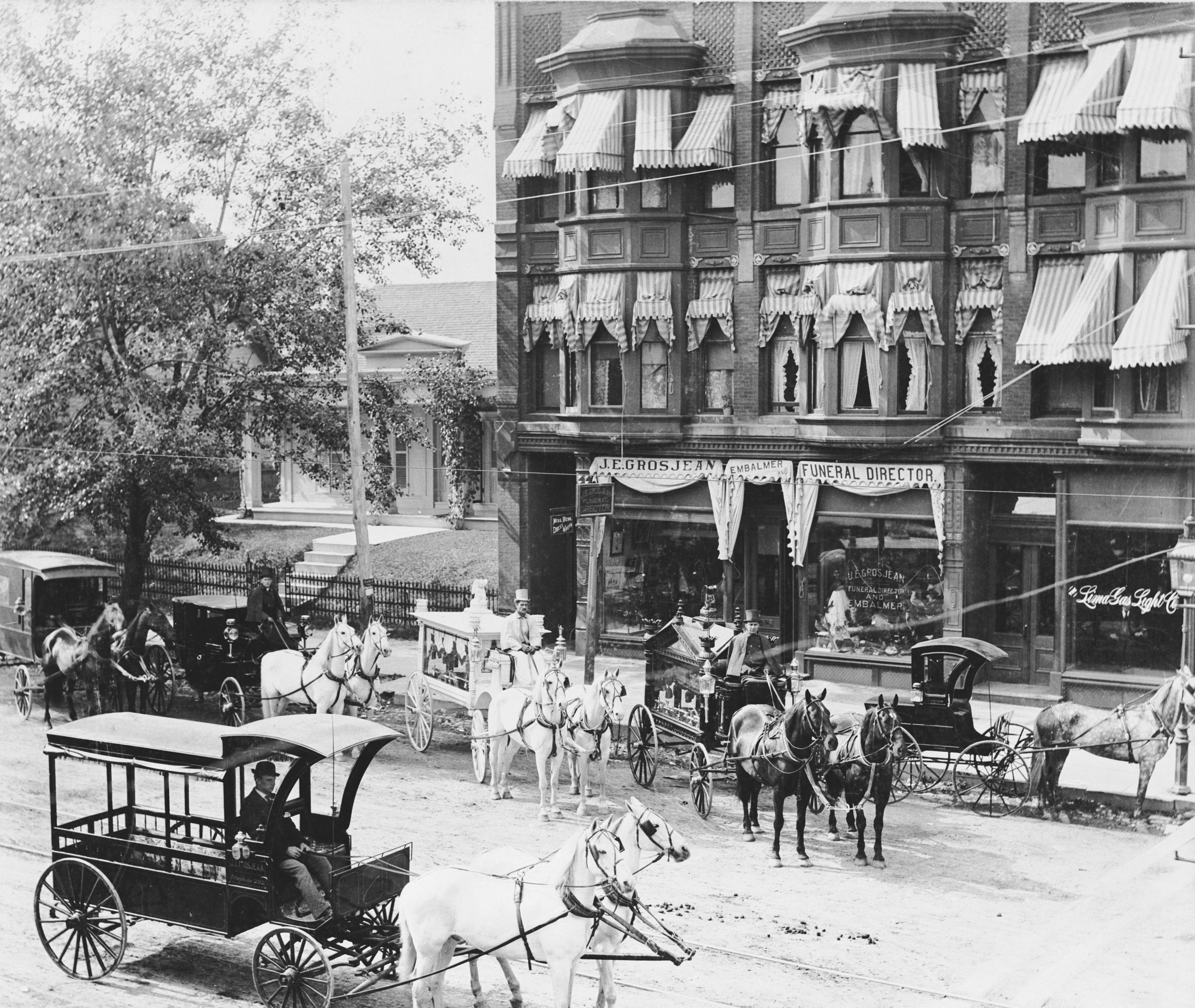

Grosjean and his family moved to Lima as it was becoming a boom town because of the oil field discovery. In December 1892, the news reported that Grosjean had opened an undertaking business on North Main Street.[12] Earlier that fall, Grosjean sold his undertaking business in Fredericksburg.[13] Just before Christmas in 1892 Nanie and the girls moved to Lima; they lived above the funeral home, according to one newspaper.[14] Ads for the business popped up in newspapers in February 1883.[15] These state that the funeral home’s location was 17 Public Square, in the southeast corner, where the Rhodes College building is today.[16] Grosjean was described as both the funeral director and embalmer.[17] The advertisement highlighted his years of experience as well as that the funeral home being equipped with the most modern embalming tools and devices.[18] For the following year, Grosjean’s advertisements state the location of the funeral home as 17 Public Square. Thus, it is unclear why the December 1892 articles stated that he was practicing from a location on North Main Street.[19] Perhaps the writer was confused between where they lived and where the funeral home was to be located, or he worked for a short time out of a North Main Street location. Over the next year, Grosjean’s business grew, and they ended up relocating to 114 West Market Street, just across the street from where the Convention Center is today.[20] At that time, he had three hearses including one that was completely white with white horses for children’s funeral services.[21] During that era, most undertakers used their hearses as ambulance transport, and Grosjean did it as well.[22] Thus, if someone was injured and needed to be taken to a hospital, they would get the undertaker and their hearse to do the transport.[23]

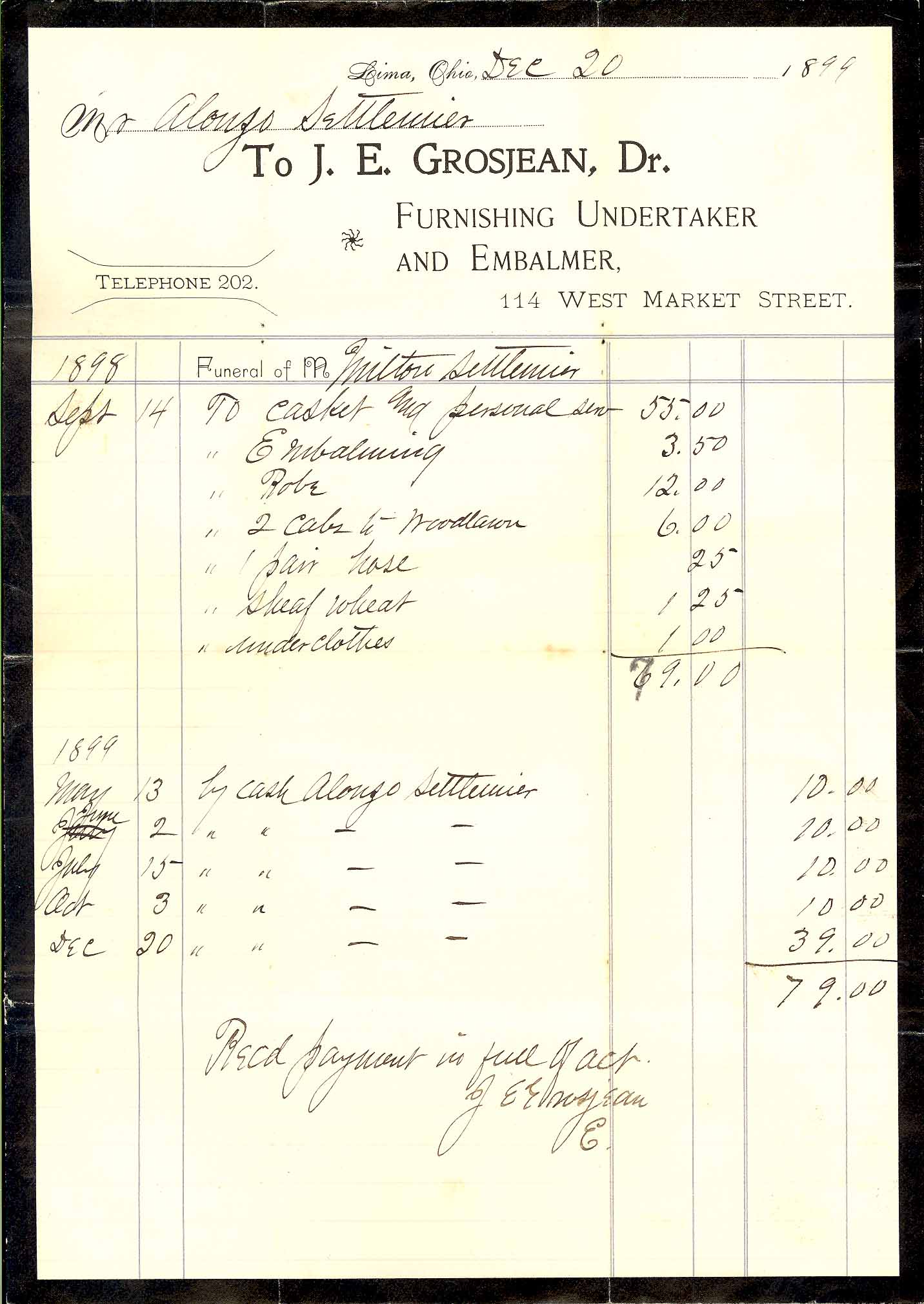

In 1898, Grosjean became an officer in Ohio’s State Funeral Directors Association.[24] He often travelled to keep up to date on the most modern practices in the funeral home industry.[25] In the Allen County Historical Society’s collection we have a bill from Grosjean’s funeral home dated September 1898.[26] The billing is as follows: $55 for the casket and personal services, $3.50 for embalming, then with the transportation and clothing the bill was $79 in total.[27] It was to be paid in installments until December 20, 1898.[28] The equivalent of $79 in 1898 to today with inflation would be $3,083.63, which is far lower than the average funeral today.[29] No doubt he kept the price low because it is believed that Grosjean made his own caskets due to his background in cabinet building.[30] During the turn of the century, Grosjean’s business interests changed to other pursuits. Therefore, in July 1901, he sold his business to his employee H. W. Bennett.[31] The newspapers were very quick to make sure Grosjean was staying in Lima; they announced happily, “Mr. Grosjean will retain Lima as his place of residence and will devote his attention to his inventive genius.”[32] Thus, after almost twenty years of being an undertaker, Grosjean decided to follow his other primary interest at that time—building mechanical “spectacular machines.”

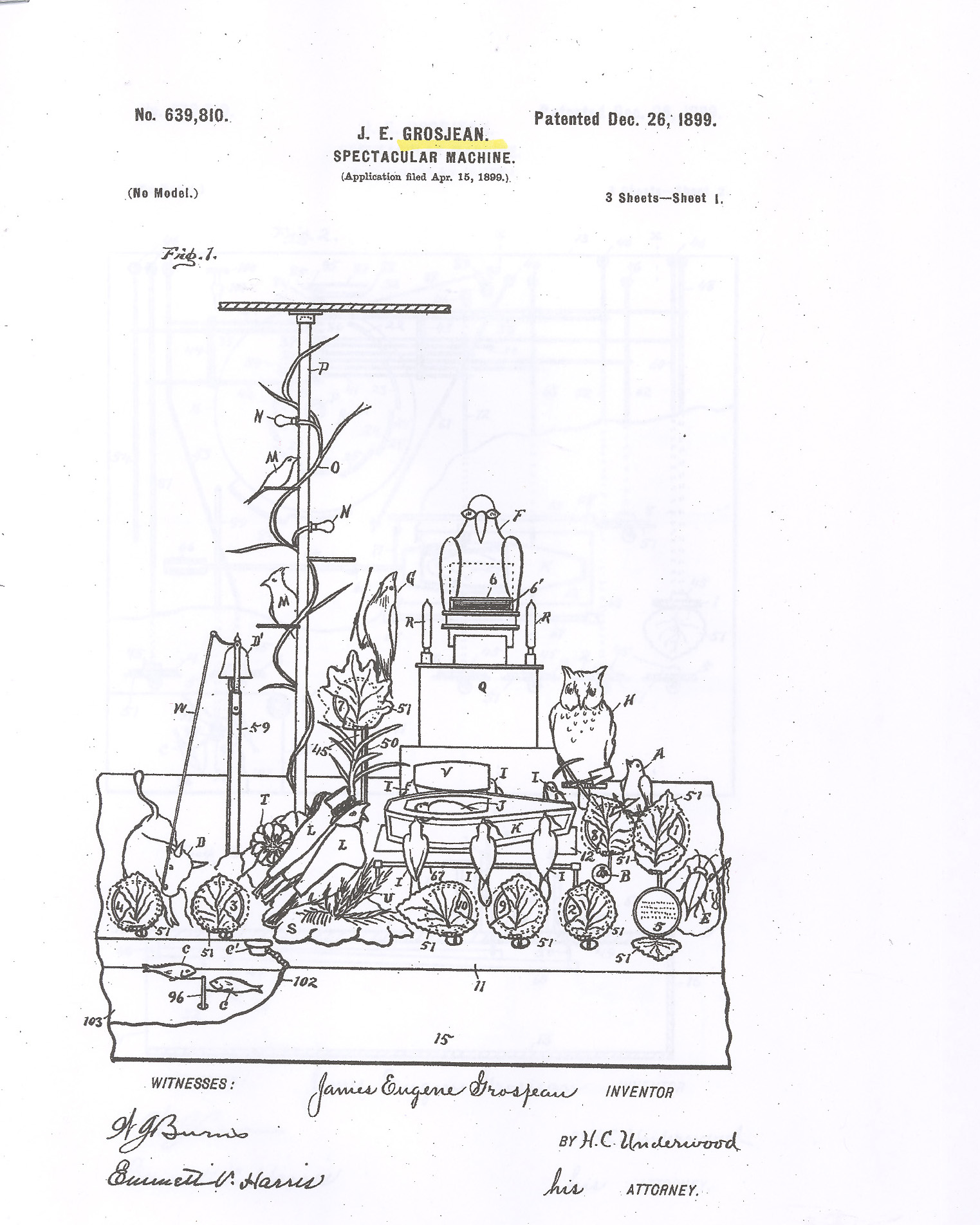

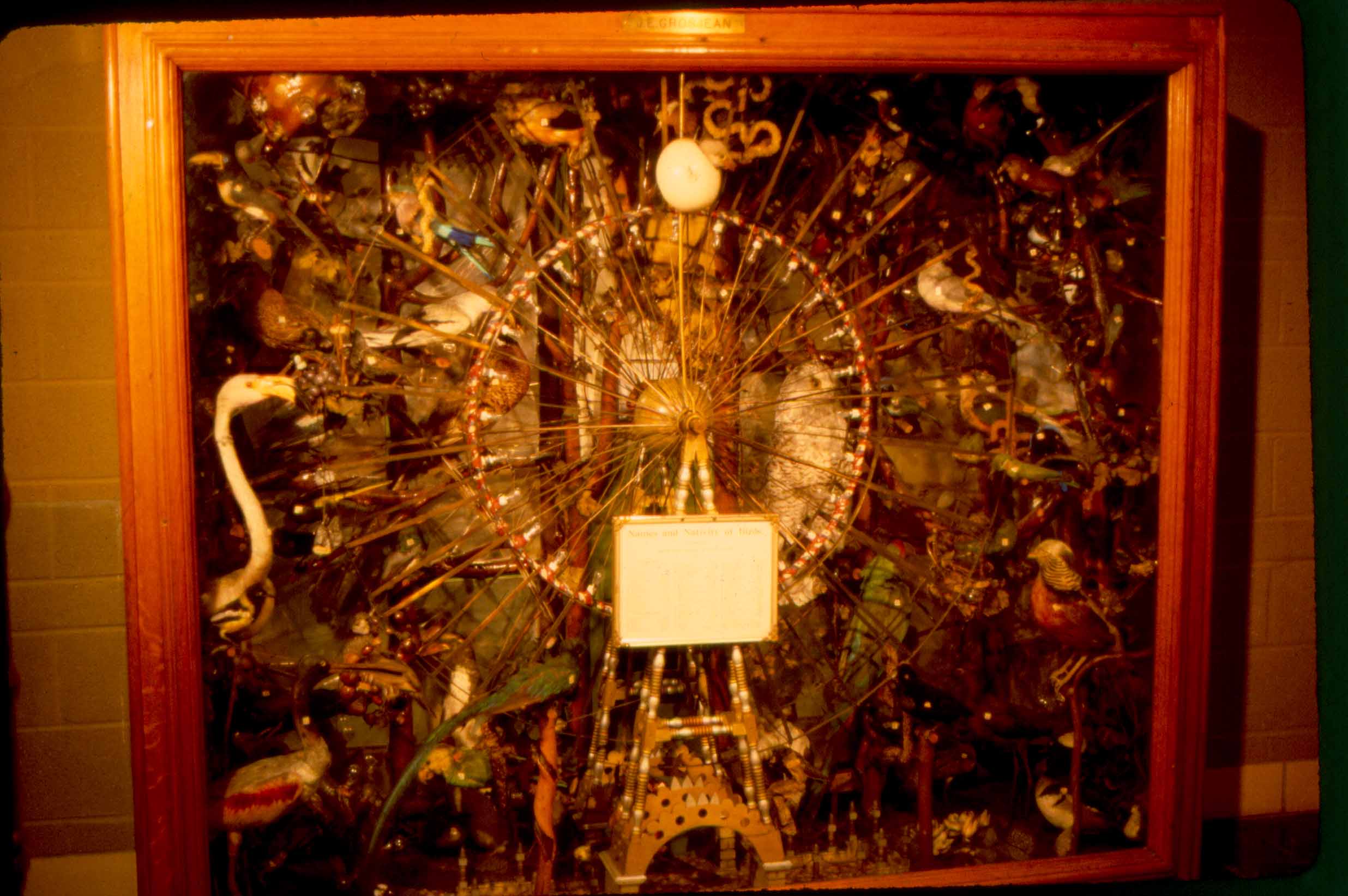

While Grosjean was still a funeral director, he had started creating his mechanical story machines that he is best known for today.[33] He would taxidermy animals, most often birds, and build cabinets to display them; usually there were electric lights and sometimes the animals moved.[34] Grosjean’s first creation seems to have been in 1896, a rare bird Ferris wheel, which he displayed in the front window of his funeral home.[35] Inspired by the Chicago World’s Fair Ferris Wheel, Grosjean created a whole scene with exotic birds enjoying a trip around the wheel.[36] He created the entire scene himself, except for the Ferris wheel which was made by John Carnes, President of Lima Locomotive Works.[37] It seems that his next display was “Who Killed Cock Robin,” which was also Grosjean’s first patent filed on April 15, 1899.[38] The patent was done not only to showcase his mechanical wonder, but also “to provide a mechanical means of illustrating a poem or play, and second, to provide means for exposing a number of placards… in succession.”[39] Grosjean wanted to create stories through his machines as well as a spectacle. Right after he completed Cock Robin it was sent to be a display window at a department store in Chicago and then a month later in St. Louis.[40] However, it did spend a few days in Grosjean’s own business window, and the public was enamored; the newspaper stated, “it is probably the finest of the many excellent things Mr. Grosjean has achieved.”[41] After Cock Robin, Grosjean created his most famous work—Noah’s Ark. This illustrates the Biblical story of the ark after the flood with birds flying, the animals exiting the ark, and a rainbow. Noah’s Ark was first put on display in a temporary museum to raise money for the city hospital.[42] No doubt that was the inspiration for Grosjean’s next business venture—a museum of his creations.

Grosjean brought this idea of a museum of his “spectacular machines” to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901.[43] Unfortunately, he was not accepted into the Pan-American Exposition, so he decided to start his own museum in Niagara Falls, New York, as a side attraction.[44] He built an electric soldier display specifically for his museum.[45] Unfortunately, we do not have any specifics about this display. He likely sold his undertaking business to pursue this business venture, because it was within two months of each other.[46] Grosjean would stay in Niagara Falls with his museum until the city decided to close all the side exhibits in late September 1901.[47] However, that business blow did not keep Grosjean down for too long. By 1902, he was exhibiting Noah’s Ark and Cock Robin in other department stores,[48] specifically in Toledo, New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh, with hopes of eventually showcasing them in the St. Louis World’s Fair.[49] It does not seem like the St. Louis World’s Fair ended up happening, because once again Grosjean became excited by another business—a shoe store.[50] That did not stop his “spectacular machine” creations. In 1905, he created a scene in the shoe store window that was a watery cave with a spinning element, showcasing the shoes the store sold.[51] There was promise at that time for many more creations, and it is unclear how many window creations Grosjean made in total. There are five main ones mentioned in most of the literature about Grosjean: Noah’s Ark, Cock Robin, the Albino Collection, the Ferris Wheel of Rare Birds, and the nearly extinct Animal and Bird Collection.[52] Four of these five are on display at the Allen County Museum. Unfortunately, in the 1913 Dayton Flood, Cock Robin was lost, so it is the only one of the main five no longer viewable.[53] In 2019, Noah’s Ark was refurbished by three of the Allen County Museum’s docents—Rick Balbaugh, Mark Billingsley, and Herb Lauer—so today you can watch a video of the Grosjean’s mechanical and magical story telling.

As mentioned, Grosjean opened a shoe store on April 5, 1904.[54] It was located at 55 Public Square, right next to where Woof Boom Radio Lima is located today.[55] The store was called Grosjean & Hall, co-owned between Grosjean and a man named Hall.[56] Grosjean & Hall specialized in corrective shoes with arch support and braces for both the working person and special occasion shoes.[57] Grosjean designed the layout of the store and its displays: Noah’s Ark and Cock Robin were included in the store.[58] During the time he owned the shoe store, Grosjean began designing different things to improve shoes. It was stated in his obituary that Grosjean was “one of the first shoe designers to design steel arches and special support braces, leather goods experts claimed.”[59] The world of shoes brought a lot of areas for innovations from Grosjean, but we will cover that next month.

This is where we will leave Grosjean’s story for now. The following article will expand on his patents and inventions, and talk about his last primary business, Lima Cord Sole & Heel Company. Likewise, it will cover the previous years of Grosjean’s life and his enduring legacy. James E. Grosjean was a tinker and a storyteller, which led him to create many “spectacular machines” and improve Allen County through his business endeavors.

Endnotes:

[1] A Standard History of Allen County, Ohio, ed. Wm. Rusler, Volume II, The American Historical Society: Chicago and New York, 1921, 131.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “New Undertaking Establishment,” ACD, December 9, 1892, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[13] Ibid

[14] “[Notables],” Lima Daily Times, December 22, 1892, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[15] “[Advertisement Undertaking Business],” Lima Daily Times, February 10, 1893, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8016/images/NEWS-OH-LI_DA_TI.1893_02_10_0001.

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “New Undertaking Establishment,” ACD, December 9, 1892, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives and “[Notables],” Lima Daily Times, December 22, 1892, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[20] “[Notables],” Lima Daily Times, August 31, 1894, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[21] “Noah’s Ark,” Allen County Reporter, Volume 15, 1959, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives, 9.

[22] Laurie Omness, “Man of Many Talents,” Lima News, July 22, 2009, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “J. E. Grosjean,” Times Democrat, June 4, 1898, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Grosjean Exhibition at the Allen County Museum.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Value of $79 from 1898 to 2025,” accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1898?amount=79.

[30] A Standard History of Allen County, Ohio, ed. Wm. Rusler, Volume II, The American Historical Society: Chicago and New York, 1921, 131.

[31] “Same,” Lima Times Democrat, July 23, 1901, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[32] “Grosjean’s Undertaking Establishment Changes Hands,” Lima Times Democrat, July 8, 1901, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[33] Lorraine Mayerson, “James E. Grosjean,” in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives, 81.

[34] Dr. Leoy Puetz, “Lima in 1900’s Bustling Locale,” Lima News, September 26, 1963, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[35] “Magnificent,” Times Democrat, December 22, 1897, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “Spectacular Machine [Cock Robin],” in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “Crowds,” Allen County Republican Gazette, February 24, 1999, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Lorraine Mayerson, “James E. Grosjean,” in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives, 81.

[43] Ibid., 81-82.

[44] Ibid.

[45] “[Notables],” Times Democrat, May 4, 1901, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[46] “Same,” Lima Times Democrat, July 23, 1901, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives and “Gaily: The Autumn Social Season Opens,” Lime Times Democrat, September 21, 1901, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8018/images/NEWS-OH-LI_TI_DE.1901_09_21_0005.

[47] “Cup,” Times Democrat, September 23, 1901, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[48] “Pittsburg,” Lima Times Democrat, October 14, 1902, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[49] “Pittsburg,” Lima Times Democrat, October 14, 1902, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives and Kevin J. Elliott “Weekend Wanderlust: Allen County History Museum,” Columbus Monthly, December 18, 2019, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.columbusmonthly.com/story/entertainment/human-interest/2019/12/18/weekend-wanderlust-allen-county-history/2035179007/.

[50] “[Advertisement Opening of Grosjean & Hall],” Lima Times Democrat, April 5, 1904, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8018/images/NEWS-OH-LI_TI_DE.1904_04_05_0008.

[51] “A Fine Attraction,” Times Democrat, May 4, 1905, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[52] “[Label on Grosjean],” in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[53] Kevin J. Elliott “Weekend Wanderlust: Allen County History Museum,” Columbus Monthly, December 18, 2019, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.columbusmonthly.com/story/entertainment/human-interest/2019/12/18/weekend-wanderlust-allen-county-history/2035179007/.

[54] “[Advertisement Opening of Grosjean & Hall],” Lima Times Democrat, April 5, 1904, accessed September 8, 2025, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8018/images/NEWS-OH-LI_TI_DE.1904_04_05_0008.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Kim Kincaid, “A Sole Man,” The Lima News, June 2, 1999, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[58] “Dainty Artistic and Up-to-Date this Store,” Allen County Republican Gazette, unknown date, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

[59] “J. E. Grosjean is Dead at 77 of Pneumonia,” unknown newspaper, December 1, 1938, in J. E. Grosjean file at the Allen County Archives.

Leave A Comment