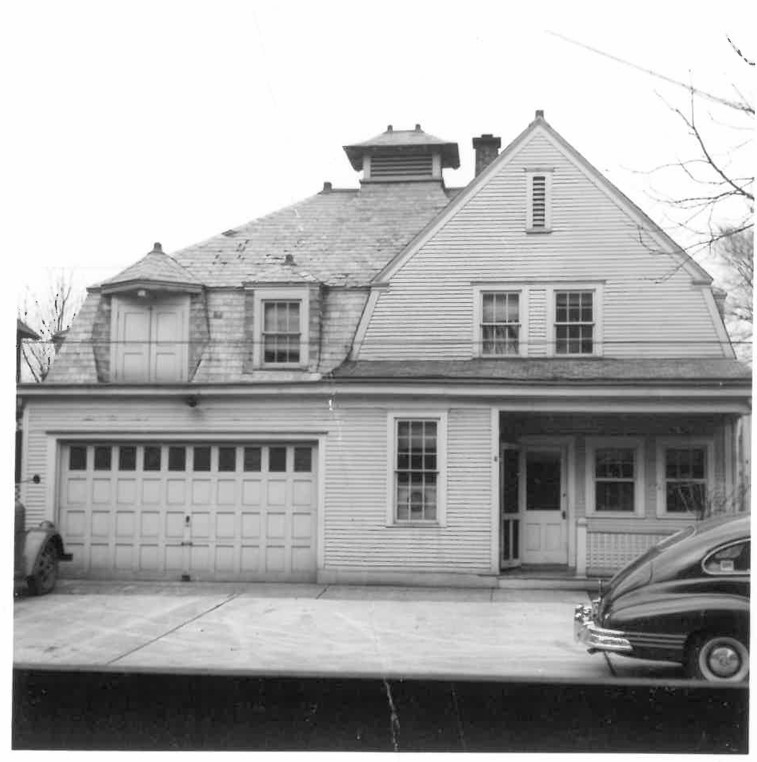

Now that we have discussed the house being built, its renovations, and the many women who called 632 W. Market St. home, it is time to discuss how the home became a museum. To begin with, we will explore how the MacDonell House came to be a part of the Museum, from its generous donors to the meticulous restoration that brought it back to its 1890s-era glory. We will also uncover artifacts and parts of the home that bear the unique stories of each of the six women, allowing us to connect with their lives and experiences. The MacDonell House, the last Victorian House on the 500 Block of W. Market St., stands today as a living testament to the foresight of those who sought to save it for future generations to learn about the past.

These forward-thinking people were Jim and Ellen MacDonell. As we remember they moved into 632 W. Market St. after Elizabeth MacDonell passed away.[1] They inherited the home in 1942 and moved in with their three daughters.[2] It should be noted that, unlike the other owners of the home, neither of the MacDonell families that lived in the house altered it in any significant way.[3] They did update it with trends and appliances of the era; however, no structural changes occurred during their time there. Their updates included vinyl flooring in the primary bathroom, which is still there, an electric stove, and a tv in the trophy room.[4] Although, according to Ellen, even with some modern additions, there was still an old fashion aspect to the house’s location that made it difficult to live in.[5] The soot coming from coal burning done at both St. Rita’s and a neighboring apartment building being the main issue.[6] In a speech about the MacDonell house and why they moved, Ellen spoke about how she would clean a cupboard and come back the next day and be able to write her name in the soot layer already deposited there.[7] In the end, she said, “I am afraid that I got a little fed up with it.”[8] With three daughters, Ellen was probably also concerned with the effects the soot would have on their health. No clear date is evident for their move from 632 W. Market St. to their new High St. home; however, the last mention of their address being the MacDonell House was August 6, 1955.[10] Likewise, the first mention in the newspaper of their address being the High St. House was them hosting a T&T Club Meeting on June 26, 1956.[11] Thus, we can deduce that sometime during those almost ten months the MacDonells officially moved out of 632 W. Market St. The only question at that point for the MacDonells was what to do with the MacDonell House.

Ellen shared in her speech about the MacDonell House that she and Jim were not quite certain of what to do with it after they moved out.[11] No doubt, the value of the house and land would have made it difficult to sell. Inspiration struck the MacDonells on one of their vacations to New England around this time. Ellen described how they always visited Colonial Homes that were furnished to the era and open to the public.[12] In that context, Jim and her reflected on how all the Victorian homes were being torn down in Lima and how they did not want the same thing to happen to the MacDonell House.[13] Ellen recalled, “Since the house adjoined the Museum it seemed like a good idea to fix it up as an example to children of what life would have been like in and around 1900.”[14] Around the time they were deciding this, their oldest daughter Ann had just graduated from Standford.[15] While there she had taken an interior design course and enjoyed it. So, Ellen and Ann decided to start on the project of fixing up the house to look like it would have around the 1890s and 1900s.[16]

Working with the Allen County Museum from then on, Ellen and Ann realized a few different things. One of the first things was that the exterior landscaping of the Museum, log cabin, and the MacDonell House needed to be blended better.[17] It needed to look like they were connected and safe for visitors to walk between. Ann headed that project, planning the exterior painting and landscaping to make the Museum’s land more cohesive.[18] The next thing they realized was that even with the MacDonell’s antiques and the Museum’s artifacts, there were not enough objects to decorate the MacDonell House the way they proposed. Since it was supposed to look Victorian, Ellen emphasized how much she wanted lots of décor and curiosities around the home.[19] Because of this, Ellen and Ann took out an ad in the paper for donations,

There is still time to donate that stored-in-the-attic Victorian piece for display in the 1890s mansion to be restored at 632 W. Market Street… Any person who has small tables and chairs, Victorian sofa, highboy, lamps or stylized bric-a-brac and wishes to give the items for permanent exhibit may contact Mrs. James A. MacDonell.[20]

From “The Book of Gifts,” which was the original inventory of the artifacts in the house, we can see that the MacDonell’s ad worked because more than one hundred different individuals donated an object or two to the house.[21] Ellen and Ann soon found themselves busy designing and renovating the MacDonell House into a Victorian home once more.

Their work was completed in 1960, and they promptly donated the MacDonell house to the Museum along with an endowment for its maintenance.[22] As was shared in Ellen’s article, the Museum held a party to honor Ellen and James’ contributions to the institution, specifically the donation of the home.[23] Likewise, James, Ellen, and Ann were recognized by the City Council of Lima for the donation of the MacDonell House. There was a resolution commending Ellen and James for donating the home to the Museum.[24] At the same time, Ellen and Ann were recognized for furnishing and designing the home back to the 19th century Victorian Style.[25] From then until the time of their passing, both Ellen and James would often give tours of the house for area clubs or visitors to the Museum, as well as financially assisting with the upkeep of the home. Because of the MacDonells’ forward-thinking, most students of the region since 1960 have had tours of the house and visitors from all around the world have also been able to see this beautiful monument of Lima’s history.

The Museum now has a place to interpret the lives of citizens of Lima from the 1890s to the 1950s because of the MacDonells’ donation. Of course, the people we focus on will most likely be the five families who lived at 632 W. Market St. Thus, it is useful to speak about artifacts and aspects of the house that connect with the women we have been discussing most of the year in these articles. When we visit the MacDonell House next, we will see the little touches or artifacts that connect each of these six women to 632 W. Market St.

Mary Banta is still the most elusive of the women of 632 W. Market St. No doubt, because she was the first, and the newspapers wrote far less about her than most of the other women. Likewise, we have no trinkets or furniture known to be owned specifically by Mary. However, she did leave her mark in the MacDonell House. The artifacts in the house that most bring Mary to mind are the gas and electric chandeliers in the front hall and breakfast room. Oral history tells us that Mary feared electricity, which was warranted in 1893. As we might remember from previous articles, the house always had electricity.[26] However, only half of the homes in America had electricity by 1925, so 632 W. Market St. was more than 30 years ahead of the times.[27] Thus, we do have to understand Mary’s aversion since, at that time, electricity was probably not as stable or dependable as it is now. All in all, those chandeliers will always be two of the artifacts that illustrate Mary’s time living at 632 W. Market St. best.

Emma Van Dyke also does not have a singular artifact that is known to be specifically hers. Her connection to the house is found in the breakfast room’s built-in sideboard. The original 1893 dining room sideboard is more the style of the late 1800s, with intricate woodworking but no motifs. In contrast, Emma’s sideboard reflects the mid-1800s with animal and harvest designs. The fox, dolphins, and abundance of fruits and vegetables were metaphors for being alive and growing before being dead and eaten in a dining room. Another metaphor they depicted was that the men were responsible for the hunting and gathering aspects of cooking.[28] Because this sideboard design was not in style, we might question if Emma intentionally chose it. Perhaps she wanted to copy the designs of her parents’ generation or display these motifs and their symbolism. Maybe the style was the specialty of the woodcarvers who built the sideboard. We will probably never know. In the end, we do know that the breakfast sideboard was among the house designs Emma and John had chosen for the 1901-1902 house renovation. Thus, the sideboard has a touch of Emma’s style and is an object that shows her time living in the home.

Even though Edna Van Dyke did not live at 632 W. Market St., there are still artifacts from her life on display in the house because her husband, John Van Dyke, was the second owner. Edna’s portrait hanging by the main staircase is the most eye-catching of her artifacts. This portrait is by an artist whose name seems to be Vendcedas de Radrau.[29] No further evidence was found on the artist, but because of Edna’s age in the painting, it seems likely that it was done between 1910-1930. Therefore, most likely done when she was singing opera in Europe. A cabinet with women painted on it sits at the top of the main staircase; this is also an Edna artifact. In the 1920s, her friend Mark Tobey painted this music cabinet for her.[30] Tobey was an American artist from Chicago; he is known as an early Abstract Expressionist who would go on to inspire artists like Jackson Pollok with his revolutionary style.[31] This object was painted before Tobey found the abstract style he was known for. The cabinet has many small drawers that are for holding sheet music. With Edna’s career, this would have been a useful piece of furniture. Hence, the portrait and music cabinet are the two artifacts that tell Edna’s story in the MacDonell House.

Unfortunately, Ida Hoover is another lady of 632 W. Market St. who does not have a specific artifact known to be hers. Because of the Hoover’s 1915 renovation, however, parts of the house have Ida’s touch. The most prominent of these is the primary bedroom’s faux fireplace. Oral History tells us that Ida liked the fireplace façade in the front bedroom, which was white with delicate swirl motifs. Regrettably for her, there was no fireplace in the primary bedroom and no ability to add one with the placements of the main staircase and primary bathroom. The story is that William added this faux fireplace, with delicate white designs, into the primary bedroom to bring that design into their room. Thus, while the fireplace is not usable, we utilize it to remember Ida Hoover’s time living at the MacDonell House.

Elizabeth MacDonell was a large donor to the Museum; thus, listing the objects connected to her in the MacDonell House would be lengthy. One of Elizabeth’s main wishes for the Allen County Museum was to be a place for learning about history and culture. This is evidenced by what Elizabeth donated, and of those, the pieces that are now on display in the MacDonell House. In the Parlor, just to the left of the settee, sitting on a display shelf, is a white vase donated by Elizabeth. Sweet little pink flowers, gold leaves, and blue bows are hand-painted onto the vase. The vase was a family heirloom owned by Elizabeth’s mother, Harriett Chaney Dalzell.[32] Likewise, in the primary bedroom, on the desk between the windows stands a glass vase with a golden base featuring a cherub. This vase was bought by Elizabeth in New York City in 1900 from Tiffany and Company. It is one of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s favrile glass vases.[33] The top of the vase looks like a flower with petals and has an iridescent purple and pink color. Elizabeth wanted the Museum to have beautiful examples of American culture and design and donated these vases because of this. It would be remiss not to mention Elizabeth’s beloved electric car, which is on display in the Museum. In 1923, Elizabeth bought a brand-new electric vehicle from the Milburn Wagon Company of Toledo.[34] She would often drive it, leaving many Lima citizens with fond memories of her running out of fuel and needing to be picked up in random areas of town. She would own the car until she passed away in 1942.[35] We can see through these examples that Elizabeth wanted to share culture and beauty with the visitors of the Museum. Some of these artifacts are showcased in the house for visitors to enjoy.

Because Ellen MacDonell helped redesign the house to the 1890s Victorian Style, she and Jim donated many objects to the house. In the book of gifts, very few donors gifted as many artifacts as Ellen and Jim. They gave items ranging from whole bedroom sets to many of the books displayed in the library. It would be hard to forget the trophy room animals obtained by Jim, which are still on loan from the MacDonell family to the Museum today. However, the artifacts that are most eye-catching and connected to Ellen MacDonell are the dining room table and chairs. The chairs are an adaptation of the Jacobean style, which would have been popular in the 1700s.[36] They most likely are recreations of the style made around the turn of the 20th century. The chairs have a very dark wood stain, intricately carved with leaf motifs and twists, as well as a red velvet seat. The dining table is no less spectacular. It has an equally dark stain and many oak leaves that make it too long to fit perfectly in the expansive dining room. The leaves have designated built-in storage in the butler’s pantry, so they are effortless to bring out and put away for events. While the whole Victorian redesign of MacDonell House should be part of how we remember Ellen, the dining table and chairs are a beautiful focal point from her time living in the house.

Thus, the MacDonell House became a Victorian 1890s house once more during the 1950s as a place for visitors to learn about the past in Lima. This was done with great thanks to Ellen, Ann (Gibbson), and Jim MacDonell, who donated and decorated the home. Today, there are still artifacts or aspects of the house that can reflect each of the six women’s lives at the MacDonell House—stretching its history from 1893 until 1960 and telling the history of these six unique and remarkable women.

[1]Jane Owen, “Museum Guides Tour the Past with Aid of MacDonell Couple,” Lima News, September 12, 1985, Cut out newspaper article in James A. MacDonell file in Allen County Archive.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Patricia Smith, “Preface,” A Detailed Resource Guide for Use with Interpreting the MacDonell House.

[4] Gay MacDonell Gibson, “The MacDonell House: 632 W. Market Street,” in MacDonell House Files at the Allen County Archive.

[5] Ellen MacDonell, “Mr. & Mrs. MacDonell on the MacDonell House,” in MacDonell House Files at the Allen County Museum.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Two Limaites to be Guests on Navy Ship,” Lima News, August 6, 1955, Accessed October 8, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7751/images/NEWS-OH-LI_NE.1955_08_06_0002.

[10] “Mrs. Stueber President of T And T Club,” Lima News, June 26, 1956, Accessed October 8, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7751/images/NEWS-OH-LI_NE.1956_06_26_0016.

[11] Ellen MacDonell, “Mr. & Mrs. MacDonell on the MacDonell House,” Typed copy of speech, in MacDonell House Inventory in the Allen County Museum Archive.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Period Pieces Needed: Donations Sought for Mansion.” Unknown Newspaper and Date [circa 1956-59], Newspaper Clipping in ACM files at the Allen County Archive.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ellen MacDonell, “Mr. & Mrs. MacDonell on the MacDonell House,” Typed copy of speech, in MacDonell House Inventory in the Allen County Museum Archive.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “The Book of Gifts: MacDonell House,” in Book of Gifts Inventory file at the Allen County Archives.

[22] “History is part of Life’s Adventure for James Alfred MacDonell,” Raymond F. Schuck, The Local Historian, Volume 5, Issue 1, March/April 1989, In James A. MacDonell File at the Allen County Archive.

[23] “James MacDonells Honored by Allen Historical Society,” The Lima Citizen, December 7, 1960, Cut out newspaper clipping in James A. MacDonell File at the Allen County Archive.

[24] “Town Topics,” edited by Bob Spellman, Unknown Newspaper and Date, Newspaper Clipping in James A. MacDonell File.

[25] Ibid.

[26] The house also always had running water.

[27] “The Electric Light System,” National Park Service, <https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/kidsyouth/the-electric-light-system-phonograph-motion-pictures.htm#:~:text=In%201882%20Edison%20helped%20form,the%20U.S.%20have%20electric%20power>, accessed February 22, 2024.

[28] William, Susan. Savory Suppers and Fashionable Feasts: Dining in Victorian America. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1996. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BozSIXPcn-cC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=victorian+buffet&ots=nHWKBws3qg&sig=w708K4BEJCQXY59-YHCJzJd4X7s#v=onepage&q=victorian%20buffet&f=false67.

[29] It is difficult to read the signature on the painting, so this is our best estimation of the artist’s name.

[30] Edna’ Music Cabinet’s Label, Allen County Museum, MacDonell House.

[31] “Mark Tobey (American, 1890-1976),” Artnet.com, Accessed October 9, 2024, https://www.artnet.com/artists/mark-tobey/.

[32] “Glass,” Catalogue Card, 308-106

[33] “Tiffany Glass Vase,” Catalogue Card, 308-41.

[34] Elizabeth’s Electric Car’s Label, Allen County Museum.

[35] “Prominent Lima Women is Dead,” Lima News, Unknown date, in James A. MacDonell File at the Allen County Archives.

[36] Allen County Reporter, XXXVII, 1981. No. 3, The Allen County Historical Society Lima, Ohio, M-12.

All photographs are from the Allen County Archive or were taken by Allen County Museum employees.

Leave A Comment