“Regardless of when a house was built and who lived in it, all homes have something in common: a need for labor to maintain the lifestyle of those who lived within.”[1] These historic, grand homes were not maintained or cleaned by their wealthy owners; it was the domestic servants who kept up the house. Homes like the MacDonell House were even built with separate living quarters for the domestic servants. In the case of all five households, we know of at least some of the domestic servants who were cooks, coachmen, maids, etc. We will meet these live-in staff members and learn what we can about their lives. Because of the size of 632 W. Market Street and the wealth of its owners, there were domestic servants who cared for the house with each of the five families, and their story helps us understand the time period better.

There is background information and definitions that need to be discussed before starting on the domestic servant history of the MacDonell House. We all know that from its conception, slavery was ingrained in the United States of America. The United States is a country whose history is built on the backs of unknown men and women who did not choose their path in life as they were sold into slavery. Of course, , we also realize that 632 W. Market Street was built in 1893, nearly thirty years after slavery was abolished in this country.[2] Therefore, no one who worked at the MacDonell House during its history was enslaved. They were instead called domestic servants, who were paid for their labor. At that time, a domestic servant typically was a term used for staff who lived and worked at the home of their employer.[3] Still, racism was just as systemic then as it is today. Often for minorities, especially people of color or immigrants, domestic servanthood was one of their only employment options, as it is still to this day for many groups. For example, in the 19th century, ninety percent of employed Black women were domestic servants because it was one of their limited options.[4] We will see that many of the domestic servants working for the five households were from minority groups.

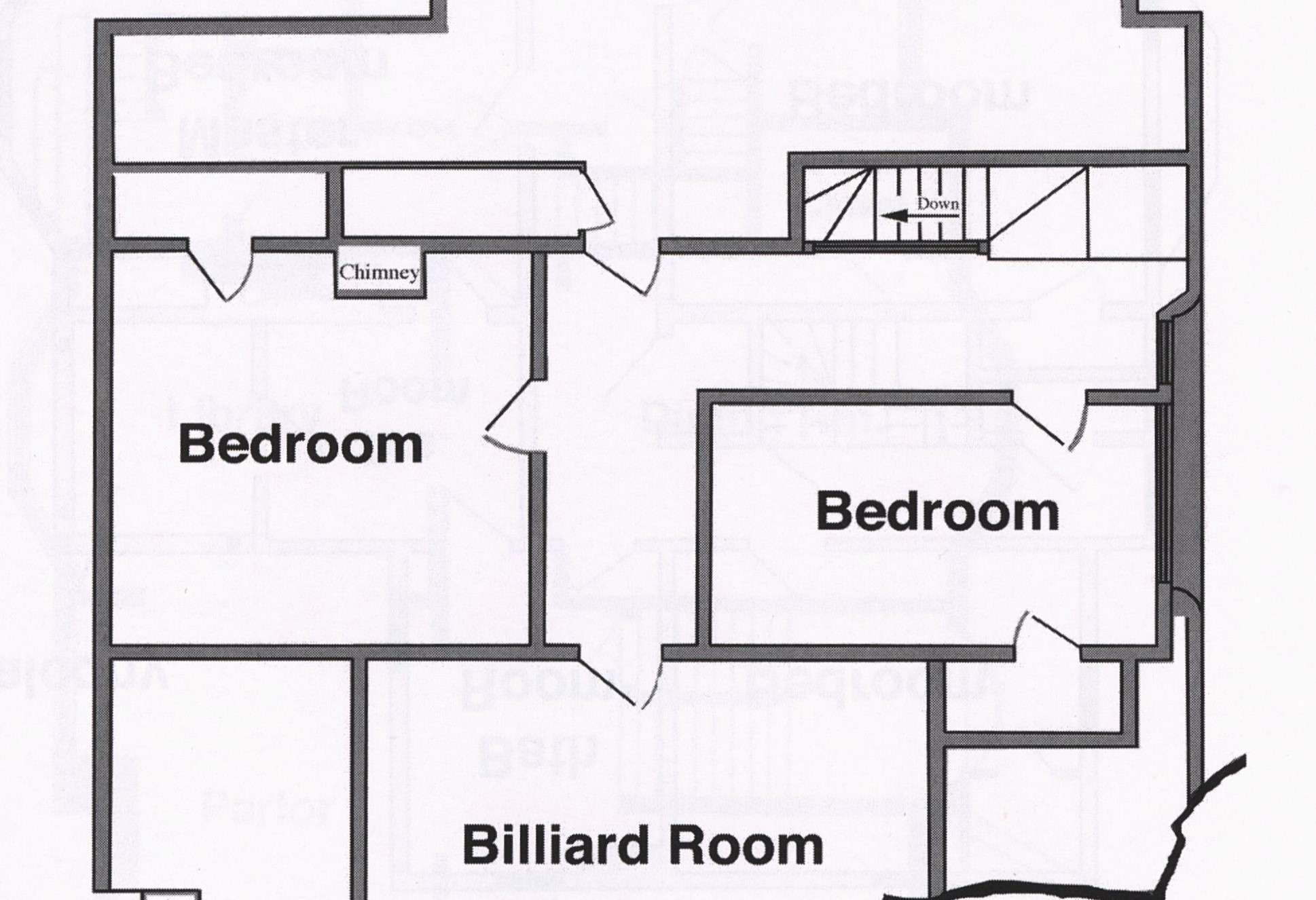

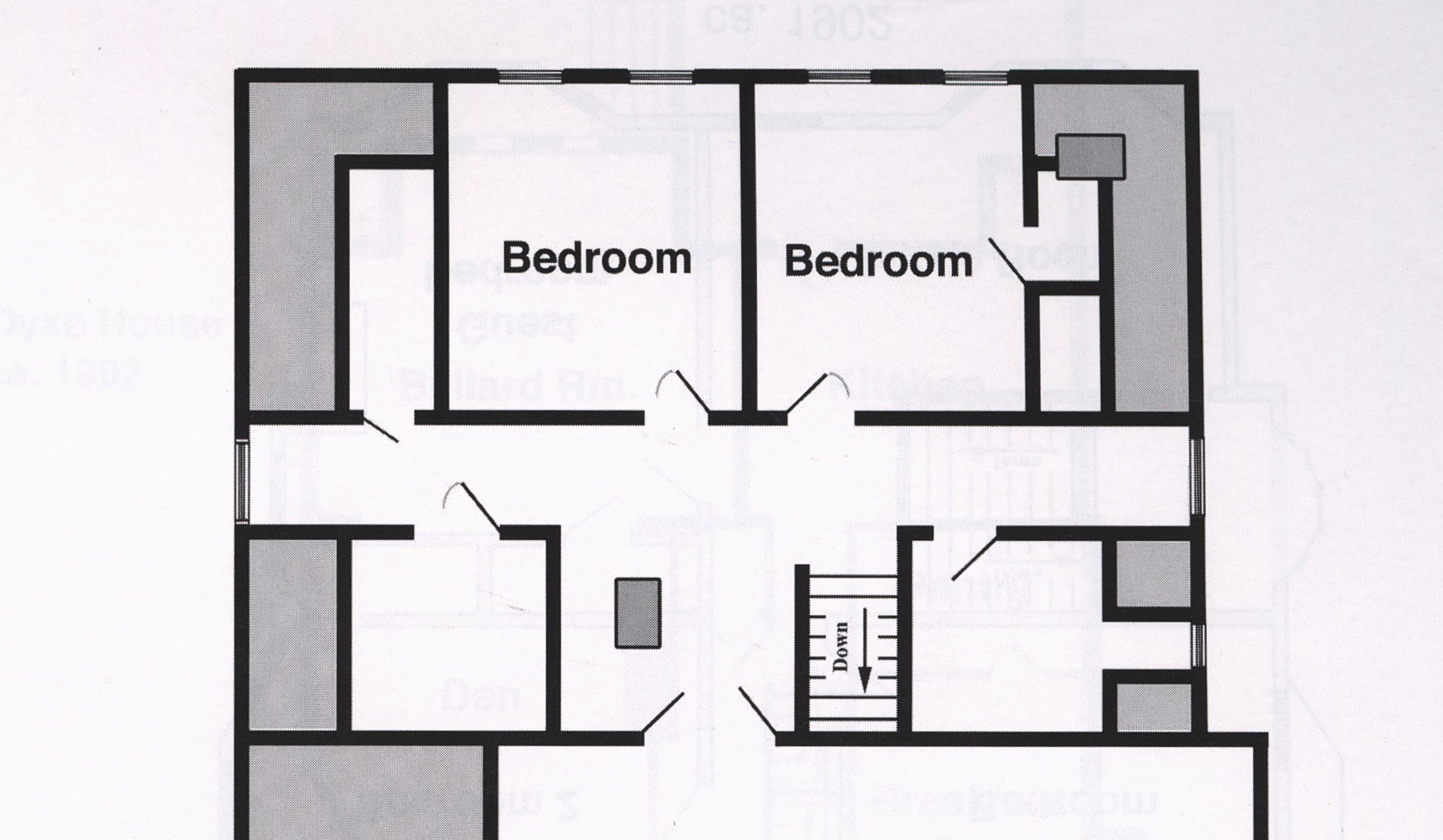

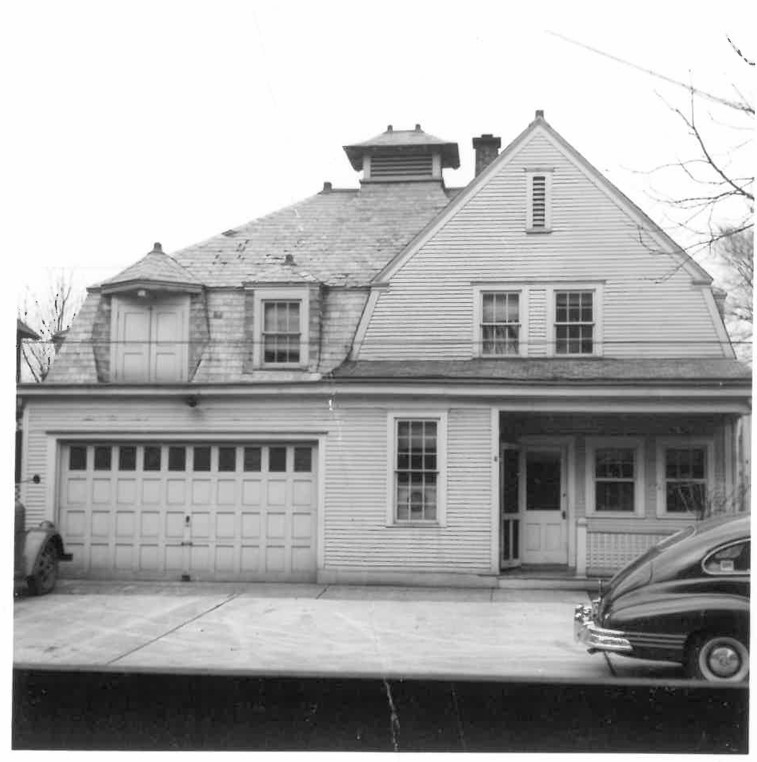

From when it was built in 1893 to its donation in 1960, 632 W. Market Street was always built for both its owners and domestic servants to live in. This can be seen with the Bantas’ top floor. Two small rooms are on either side of the upstairs as quarters for the domestic servants. When the Van Dykes renovated the home in 1901-1902, they expanded even more with domestic servants in mind. The date the carriage house was built is somewhat murky; either built for the Banta or the Van Dyke household. All in all, the carriage house was outfitted not only as a place for the carriage and horses but also as an abode for a family who would work as domestic servants for the homeowners. One of the extensive changes the Van Dykes made to the house was on the top floor, making it longer with the rest of the house, and it included two bedrooms for live-in staff. One of the three bathrooms the Van Dykes added was for their domestic workers, too. Located in the basement, the bathroom had a tub, toilet, and sink. However, not all the additions were made for the comfort of the staff. The Van Dykes also had a call button system installed in both the breakfast room and dining room, so they could call their staff without having to raise their voices. In 1915, the Hoovers would modernize some things that their live-in workers used in most cases, such as the soot elevator, coal door, and laundry chute. From all these examples, we can see that the MacDonell House was always built for the addition of domestic staff.

Unfortunately, there is no record of whether the Bantas had live-in staff while living at 632 W. Market Street. Most often, these records are gained from US census information, and because the Bantas lived in the house from 1893-1897, there is no census data about their time there. With the two bedrooms and the family’s wealth, they likely had domestic servants or help who lived outside of the home. The Bantas had two different robberies at the house in 1896; in the newspaper articles, it is indicated that no one was home.[5] This does not mean they did not have staff, but it seems more likely that they did not live in the home. In the 1910 census, when Frank was living elsewhere with his second wife, the Banta household had a housekeeper named Ida.[6] The census tells us Ida was Black, eighteen years old, and the housekeeper.[7] Later, during Frank Banta’s third marriage, the Bantas had indentured girls. At that time in Ohio, it was legal for families to create an indenture agreement with children from orphanages.[8] The family would provide for the child’s needs and schooling, and the child would help around the house.[9] Of course, we do not know how such arrangements went, whether the child was well taken care of or not. In any case, the Bantas had two indentured girls who lived with them over the years. Their first, in 1911, was Ella Bradley-Profitt, who was listed as a person of color in the Miami County Ohio’s Children’s Home Index.[10] Ella had been born on June 29, 1895, and was fifteen in April of 1911 when she became indentured to the Bantas. There is no information about Ella’s life with the Bantas or how long she was indentured with them. What we do know is that they got another indentured girl in August of 1918.[11] Her name was Mary Elizabeth Marshall; the index did not note her race. Mary had been born on December 14, 1902, and was fifteen at the time she became indentured to Frank and Cora Banta.[12] Again, we have no information as to how her life was or how long the indenture lasted. However, the examples of Ida, Ella, and Mary show us that there were domestic staff in the Banta household at different times.

As one of the wealthiest families to live at 632 W. Market Street, the Van Dykes, naturally had live-in staff. The first was Kin Ling Nip, who probably was John W. Van Dyke’s assistant and valet. Kin emigrated to the US from China in 1879 when he was a child, and at the time of the 1900 census, he was twenty-eight.[13] According to the census, he lived in the house with John and Emma. In addition to Kin, the Van Dykes had a coachman named George Bond and his wife Martha who lived in the carriage house.[14] Both George and Martha were Black and were respectively thirty-two and twenty-five according to the 1900 census.[15] There was not any record of Martha holding a job at the house in the census; though, it seems likely that she did as either a cook or a maid. While Kin might have cleaned to some extent, because of the parties the Van Dykes held, it would be surprising if they did not have both a cook and a maid. Of course, these positions might have been held by staff who did not live at the house; thus, they were not on the census. We might remember that the Van Dykes moved back to Pennsylvania around 1903-04, and the house was unoccupied until 1915. During that period, John paid George Bond as a caretaker for the house.[16] In the 1910 census, both George and Martha were still living in the carriage house.[17] In a news article around the time the Hoovers bought the house, July of 1915, a reporter noted that George made around $2,400 a year watching over the house.[18] According to the CPI Inflation calculator $2,400 in 1915 would equal around $75,000 today.[19] Of course, that is if the reporter got George’s salary accurately, but it would have been quite a living wage if correct. Likewise, this tells us that George and Martha Bond lived on the property longer than most of the owners.[20] Going back a few years, the 1910 census indicates that Kin no longer lived with John as a domestic worker.[21] Perhaps he still worked for John but lived elsewhere, we will never know. However, in the 1910 census, John had a butler named John R. Johnson and a maid, Mary A. Morris, both were recorded as Black in the census.[22] Again, we do not quite get specifics about the lives of the Van Dykes domestic servants, but we know their names, ages, occupations, and in some cases, wages.

The Hoovers also had live-in staff during their time at 632 W. Market Street. William D. Shorcraft and his wife Nora lived in the carriage house according to the 1920 census.[23] They were recorded as people of color; William was forty-seven, and Nora was forty-two. William was a chauffeur instead of a coachman because the Hoovers had a car, not a carriage. Nora was listed as a servant, so she could have been a maid or cook. By the 1930 census, William and Nora were no longer living with the Hoovers, nor were any other domestic servants.[24] We might remember that at that time, the Great Depression was hitting the Hoovers financially, so that could be why they had no domestic servants. However, before living at the MacDonell House, the Hoovers did not have live-in staff in the 1900 census.[25] Thus, it could be the size of 632 W. Market Street that contributed to their need for domestic servants, or it was a status symbol they kept up like the other owners.

Both the Elizabeth MacDonell and Jim and Ellen MacDonell households had live-in staff while residing in the home. Before moving into 632 W. Market Street, Elizabeth had domestic servants. In the 1920 census, a woman named Annie Brown lived and worked at Elizabeth’s home. Annie was recorded as Black, forty-seven years old, and a servant in the household.[26] The next census brings us to Bernadine J. Kahle, who would work for the family for the next thirty-plus years.[27] Bernadine, better known as Dini, was white and is the only domestic servant we have photographs of. She moved with Elizabeth to the MacDonell House in 1932, and would become Jim and Ellen’s housekeeper in 1942 after Elizabeth passed.[28] Just like the Hoovers, Jim and Ellen did not have any domestic staff until they moved into the MacDonell House.[29] Last month’s article mentioned how difficult Ellen found it to keep the house clean, so no doubt that was one of the reasons they found it necessary. Gay MacDonell Williams, Jim and Ellen’s second daughter and former ACHS Board President, wrote a lovely remembrance of living at the MacDonell House as a girl. One of the things Gay highlighted was Dini and her life. She wrote fondly, “Dini did all the cooking and DID NOT WANT anyone in her kitchen!”[30] Dini was the cook of the house; seemingly even Ellen knew it and stayed out of her way. Likewise, Dini did not live in the carriage house or even upstairs in the servants’ quarters. Her bedroom was the northwest corner room, between the two bathrooms, in the room we call the children’s room today.[31] Gay also shared more about what Dini liked to do with her free time. Dini was a devout Catholic, going to St. Rose Catholic Church for mass several times a week.[32] Gay describes this as one of Dini’s difficulties with moving to the High Street house with Jim and Ellen. It was simply too far from St. Rose for her to walk easily.[33] Likewise, Dini did not like cooking on the new kitchen appliances, which were electric.[34] So it was not long after the move that Dini retired and bought a home in Fort Jennings close to her family.[35] Unfortunately, the 1960 census has not been digitized by the National Archives. Hence, no further information about the MacDonells having domestic servants beyond 1950 was able to be obtained. Overall, Dini gives us the last and most complete information on a domestic servant living and working at 632 W. Market Street.

Each of these domestic servants spent their time cooking, cleaning, and transporting the households of 632 W. Market Street. Because of this, the MacDonell House also needs to tell their stories. In many cases, the live-in staff consisted of minorities; knowing this, we better understand the demographics of those who lived at the home and in Lima at the time. Due to the size of 632 W. Market St. and the affluence of its owners, each of the five families that lived there had domestic servants to maintain the house. Likewise, knowing about the people who filled these positions is crucial to accurately understand the history of the MacDonell House.

Endnotes:

[1] “Listening for the Silences” by Jennifer Pustz, in Reimagining Historic House Museums: New Approaches and Proven Solutions edited by Kenneth C. Turino and Max A. Van Balgooy. 162.

[2] Slavery was abolished December 6, 1865, by the 13th amendment ratification in the United States Constitution.

[3] “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door” by Patricia Smith. In Allen County Reporter, special issue, Vol. LXVII, 2013. Allen County Historical Society, 18.

[4] “Black Domestic Workers,” Unknown Author, WAMS New-York Historical Society, Accessed October 28, 2024, https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/labor-and-industry/black-domestic-workers/.

[5] “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door” by Patricia Smith, 18.

[6] “Frank Banta, in the 1910 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/21088854:7884?tid=&pid=&queryid=1eac3a15-8614-400a-a7e4-885e2a8f2aba&_phsrc=ppw387&_phstart=successSource. It also should be noted that they did not have any domestic servants noted in the 1900 census because that was when they were renting a room because of Mary’s health. “Frank Banta, in the 1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/38656660:7602.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door” by Patricia Smith ,43.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Ella Bradley-Profitt,” in Miami County Ohio Children’s Home Index, 1879-1930, Book 1, Accessed February 19, 2024, https://thetroyhistoricalsociety.org/m-county/c-home/ch-abcde/0859.htm.

[11] “Mary Elizabeth Marshall,” in Miami County Ohio Children’s Home Index, 1879-1930, Book 1, Accessed February 19, 2024, https://thetroyhistoricalsociety.org/m-county/c-home/ch-jklm/1128.htm.

[12] Ibid.

[13]“John W. Van Dyke, in the 1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/38658249:7602?tid=&pid=&queryid=81243fe9-9496-44a1-a336-38859f6c6ce6&_phsrc=ppw344&_phstart=successSource.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door” by Patricia Smith, 26.

[17] “George A. Bond, in the 1910 United States Federal Census,” Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/21086068:7884?tid=&pid=&queryid=dd55b089-840a-4113-96fd-81065fc53e9a&_phsrc=ppw346&_phstart=successSource.

[18] Unknown Article Title or writer, 1915, In MacDonell House Interpreter Research.

[19] CPI Inflation Calculator set for $2,400 in July of 1915 to September of 2024, Accessed September 30, 2024 https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=2400&year1=191507&year2=202409.

[20] We know that the Bonds lived in the house from 1900-1915, and they could have moved in with the Van Dykes as early as 1897. That means the lived in the house for between 15-18 years, only the Hoovers lived in the home close to that, from 1915-1932, 17 years.

[21] “John W. Van Dyke, in the 1910 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/25244268:7884.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “William F. Hoover, in the 1920 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/76312386:6061?tid=&pid=&queryid=9b15a5d2-40a6-4b71-b41a-79d3e81c2e3f&_phsrc=ppw355&_phstart=successSource.

[24] “William F. Hoover in the 1930 United States Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024 , https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/74955156:6224?tid=&pid=&queryid=c384475f-4b11-4450-beaf-25a6decf3088&_phsrc=ppw357&_phstart=successSource.

[25] “William Hoover, in the 1900 United States Census,” Ancestry.com Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/38646426:7602. Unable to find William’s 1910 census record.

[26] “Elizabeth M. MacDonell, in the 1920 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/76313414:6061?tid=&pid=&queryid=496df919-929b-45c6-8880-9b62689abe8e&_phsrc=ppw375&_phstart=successSource.

[27] “Elizabeth MacDonell, in the 1930 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/74954508:6224.

[28] “Elizabeth MacDonell, in the 1940 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/36139021:2442, and “James A. MacDonell, in the 1950 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/204153557:62308?tid=&pid=&queryid=80dce34d-fab2-4c6a-8f93-b554a573737b&_phsrc=ppw364&_phstart=successSource.

[29] “James MacDonell, in the 1940 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Accessed October 29, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/36152252:2442.

[30] “MacDonell House, 632 W. Market Street,” Gay MacDonell Williams, September 2022, In MacDonell House Files at the Allen County Archives.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

Image Credit:

“[House maid ironing a lace doily with GE electric iron],” c1908 Dec. 26., LOC, LC-USZ62-67635 (b&w film copy neg.), <https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004665710/>.

Marian Post Wolcott, “Negro domestic servant. Atlanta, Georgia,” 1939 May, LC-USF34-T01-051738-D (b&w film dup. neg.), <https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017800961/>.

“Training Servants,” 1873, Wood Engraving, LC-USZ62-39056 (b&w film copy neg.), <https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2022648422/>.

All other images come from the collections of the Allen County Museum and Allen County Archives.

Leave A Comment