The Great Expansion

The Bantas switched houses with the Van Dykes in 1897, making them the second owners of the house at 632 W Market Street. [1] Before this, the Van Dykes had built a home at 557 W Market Street when Standard Oil sent John to work in Lima in 1886.[2] While not on the “Golden Block,” 557 W Market Street is a part of the block by the museum near where the McDonalds is today. The Bantas would move into that house for a short time after they switched with the Van Dykes. . Of all the families and individuals who owned the house, the Van Dykes would make the most changes to its structure and layout. Their renovation would occur sometime between January 1900 and December 1902,[3] and they would build on or significantly transform over 3,000 square feet of the home.[4] One of the difficulties when sorting out what is original to the Banta build and what was changed by the Van Dykes is that only the original Banta blueprints and the Hoover expansion schematics are available today.[5] Thus, we have no written record of the changes and additions made by the Van Dykes. The saving grace is that they constructed whole rooms onto the back of the house; therefore, the design styles of those rooms obviously originated from the Van Dyke expansion. From there, we can extrapolate a little bit on what matches what era of the house

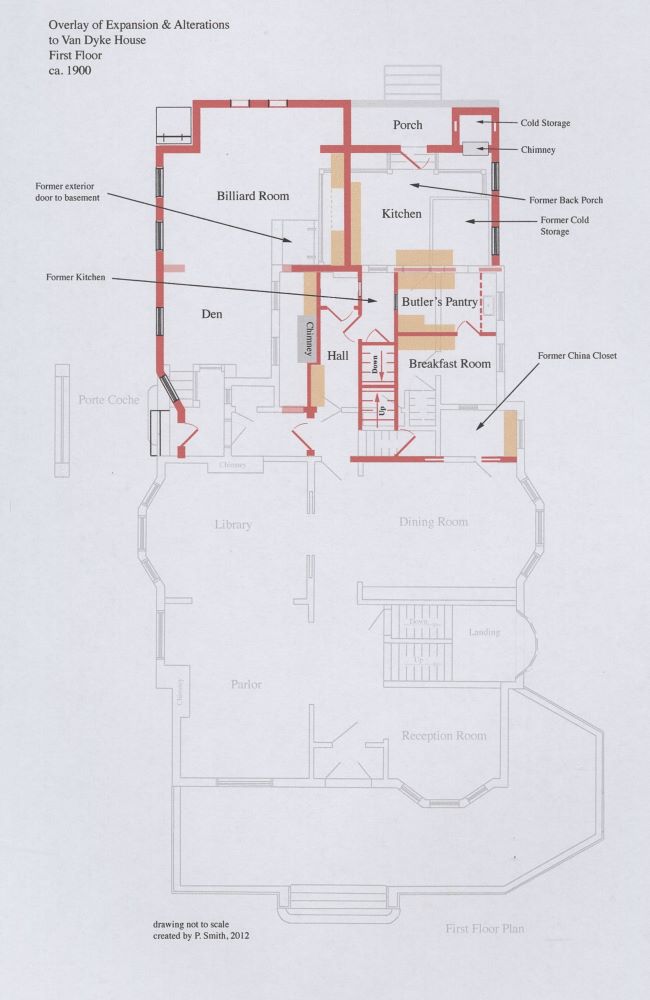

We will first look at what the Van Dyke renovation changed about the layout of the home. The red lines in these plans are the new changes superimposed on the grey lines, which indicate the old layout. As you can see, the front of the house on all three levels did not change nearly as much as the back of the house. The changes are a mixture of creating more space and general modernization. The Van Dykes lived in the house for around three years before the renovation took place; consequently, they would have known what they needed to update and what they did not.[6]

Starting with the first floor, we have to keep in mind John Van Dyke was born in 1849, so he was either fifty or fifty-one when the renovation begins. Hence, it makes sense that he wants the addition of a billiard room and a den on the first floor to create a home office or perhaps a “man cave.” His visitors can enter on the west side of the house without disturbing his wife or servants. Then, they built the breakfast room for an additionaland less formal room to eat in. Based on the size of the parties they held, it is also logical to assume it was used by guests as well. The more modern touches included cold storage, butler’s pantry, large kitchen, and foot-operated call buttons in both the breakfast room and dining room. In the basement, the Van Dykes added a bathroom, presumably for the servants, as well as a laundry.[7] To compensate for further water needs of the house, they had to install two cisterns.[8] These were unfortunately made out of lead, which was typical around the turn of the 20th century—luckily the last owners of the house took those out.[9] Today the first floor and basement have the same basic layout as the Van Dykes’ renovation.

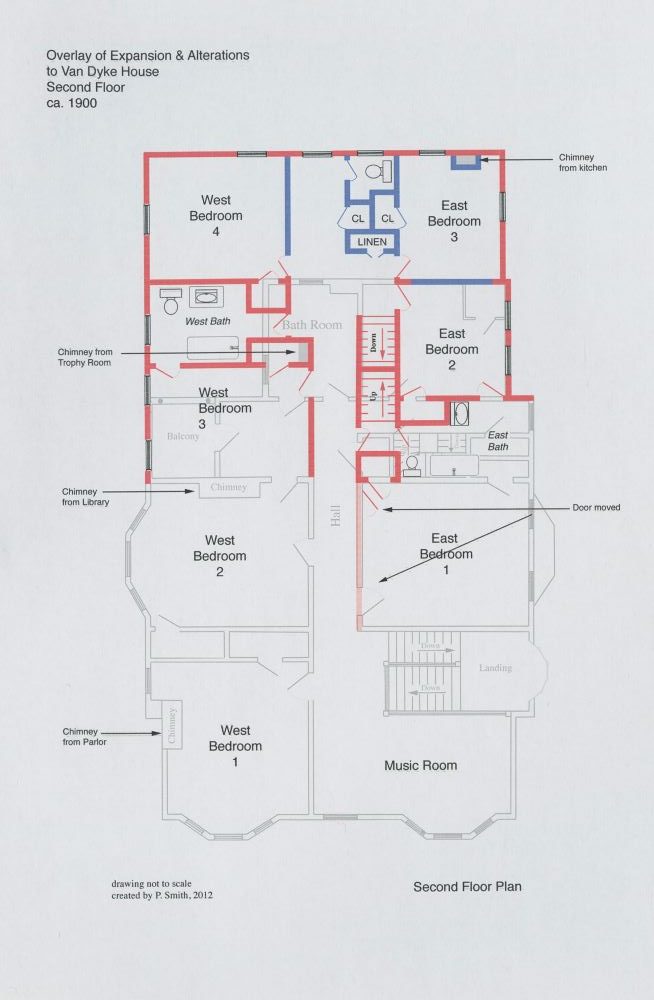

On the second floor, the back staircase that connects all three floors was also changed considerably. Instead of being a winding staircase, like the Bantas designed, it was now straight—going from the first to second floor and another staircase going from the second to third floor. An oral history explains that John did not like the inefficiency of the curving staircase. No doubt, the straight staircases were easier for the household, servants, and guests to navigate. They also became grander, yet another beautiful design element of the house. Likewise, the Van Dykes added four rooms to the second floor. These were presumably guest rooms since they had no children. Thus, the back staircase was not only the easiest way to the ballroom for parties but also the clearest path for any guest going to their rooms or the guest bathroom.

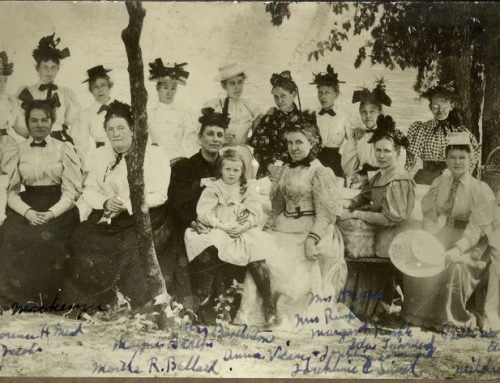

While it has often been commented that all the bedrooms planned by the Van Dykes did not make sense because they did not have any children, the most logical answer to this, is that they needed more rooms for guests. Not only was Van Dyke influential in the oil industry, but they also integrated themselves very quickly into Lima society and were both originally from out of state. We also know they had large parties, a topic we will touch on in more detail in the next newsletter article. Due to all of these factors, it is safe to assume they frequently had guests.

Based on the layout of the house, it would not be surprising if East Bedroom 2 was a sitting room since it opens into the primary bathroom and East Bedroom 1 was the primary bedroom. The Van Dykes also had two more bathrooms built on the second floor: the east bath or primary bath and the toilet on the north wall. Unfortunately, based on the Hoover schematics, we cannot tell if there would have been a sink in this powder room or not.[10] It seems unlikely that the Van Dykes would simply put a toilet in a room without a sink, but it does make an intriguing room on the layout. It should also be noted that the Van Dykes outfitted the west bath with new fixtures and marble while putting the Bantas’ fixtures in the primary bathroom and keeping that design more sedate/simple. This is a classic Victorian-era design precedence; make the areas the guests see the most beautiful parts of your home.

The third-floor expansion gave the Van Dykes more places to entertain and significantly more storage to the house. They tore down most of the walls from the Bantas’ design and turned the front of the upstairs into one big ballroom with built-in benches and plenty of room to dance. They also included four closets, and one of them was even a cedar closet with a built-in storage trunk.[11] Just like the original design, they had two bedrooms on the top floor constructed, moving them to the north of the house and placed above the new addition. These bedrooms were presumably for live-in servants. It is logical to discern that most of the home’s renovations were done for additional space and modernization. The Van Dykes changes echo the current layout and design more than any other family that lived there.

Depsite the renovations, the Van Dykes did continue with some of the original Banta design elements. It is one of the most interesting things about this renovation. As we discussed in the Banta House article, the home was built in the Victorian Shingle Style. When the Van Dykes’ renovated it seven years later, there was a new house style that influenced the house—The Arts and Crafts Style. In many ways, the Victorian Shingle Style can be seen as the transition from general Victorian styles to the Arts and Crafts Movement. When looking for comparisons during the early 1900s, the two styles are almost too similar to compare. However, Arts and Crafts eventually evolved into Mission, Craftsmen, and Mid-century styles. Nevertheless, the early designs are incredibly similar, and the Van Dyke house is a great illustration of these.

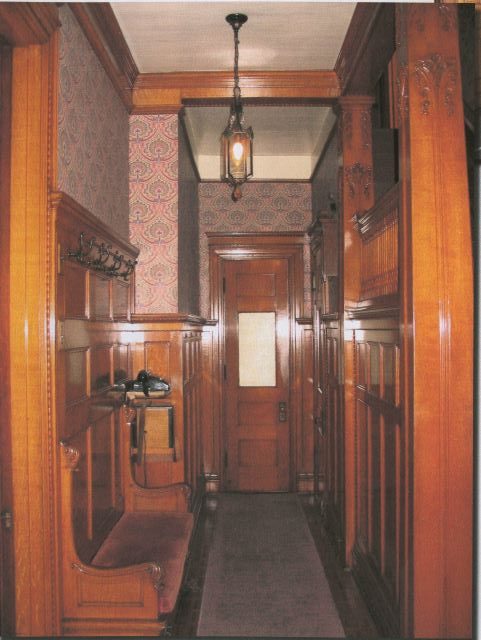

There is a lot of blending between the spaces from the original Banta layout to the Van Dyke expansion. This is not to say there are no new flourishes, but when walking from the dining room to the back hall, it is evident that the design choices were made to make the extension blend with the original parts. This is best illustrated by the front hall and the back hall. They both have a type of wainscoting called a “raised panel wainscoting,” but they are not exactly alike if you look closely.[12] The dimensions are probably the easiest way to see they are not quite the same. The front hall panels are slimmer, and the back hall panels are a bit wider. Hence, we get more repetition of the pattern in the front compared to the back. There is also more of a technical difference between them. The front hall’s raised panel insert comes out from the wall, while the back hall’s just a flat panel. These are minute differences in the grand scheme of things, but they help us see what is original to the Banta home and what is part of the Van Dyke renovations.

One thing that is very easy to determine is that the Van Dykes’ had crafted the coffered ceilings. Only one room from the original portion of the house has any ceiling adornment. That is the dining room, which has carved, wooden beams running horizontally across it. Because of the built-in sideboard these beams are likely original. On the other hand, the coffered ceilings are only in the new additions, namely the breakfast room and the den/billiards room. Coffered ceilings are perhaps the perfect example of how the Victorian Shingle Style is so transitionary between the Victorian styles of the 1800s and the design styles of the early 1900s. Curtis Rist wrote about coffered ceilings, “Tastes changed by the 1870s, with a Victorian revival of the Old English style… coffered ceilings began to appear in large entrance halls as well as other rooms. They later became features of Shingle Style houses.”[13] Coffered ceilings were not a highlighted design of the Victorian styles until the Victorian Shingle Style. However, today, we in America relate them more to The Arts and Crafts, Craftsmen, and Mission Styles. One of the differences in woodworking between the styles is that The Arts and Crafts Style typically has far more nature motifs. In the Banta house article, we talked about the Acanthus design that popped up in several places in the house; there, it was attributed to being inspired by neoclassical motifs. This seems even more likely since the rest of the Bantas’ design features in the woodworking are repetitive patterns and are not inspired by nature. That is not to say there are not repetitive patterns in the Van Dykes’ coffered ceilings, but in the corbels we see something new. There is the Acanthus leaf design, but then we get flowers and swirls that harken more to the Arts and Crafts Style. This is all done in the same wood tones in a style relative to the Bantas’ woodworking, so it is almost seamless. Except, we must note these slight differences where the house’s design was moving towards the early 1900s design styles and away from strictly Victorian inspiration.

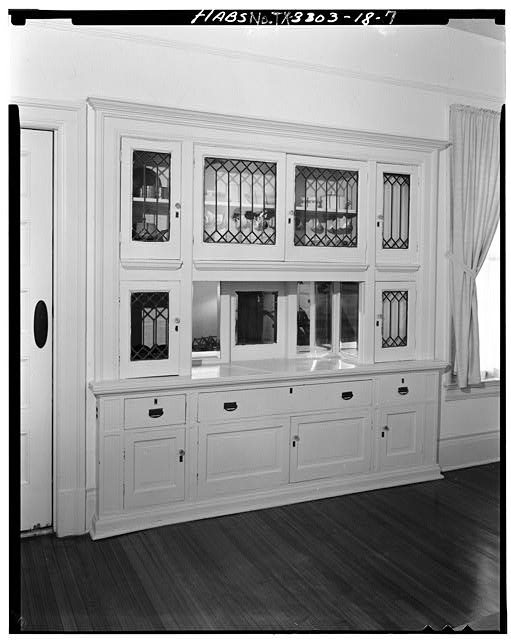

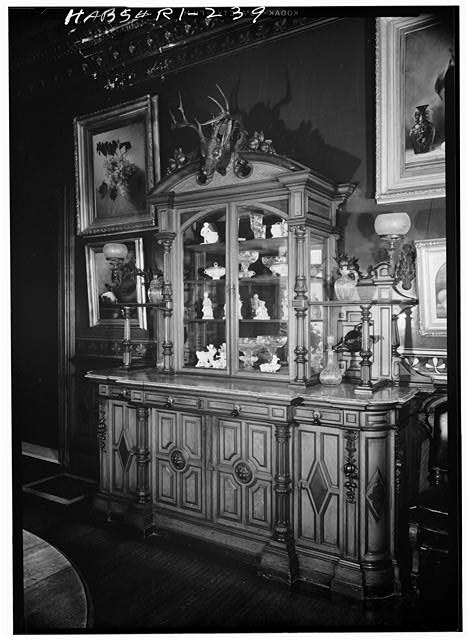

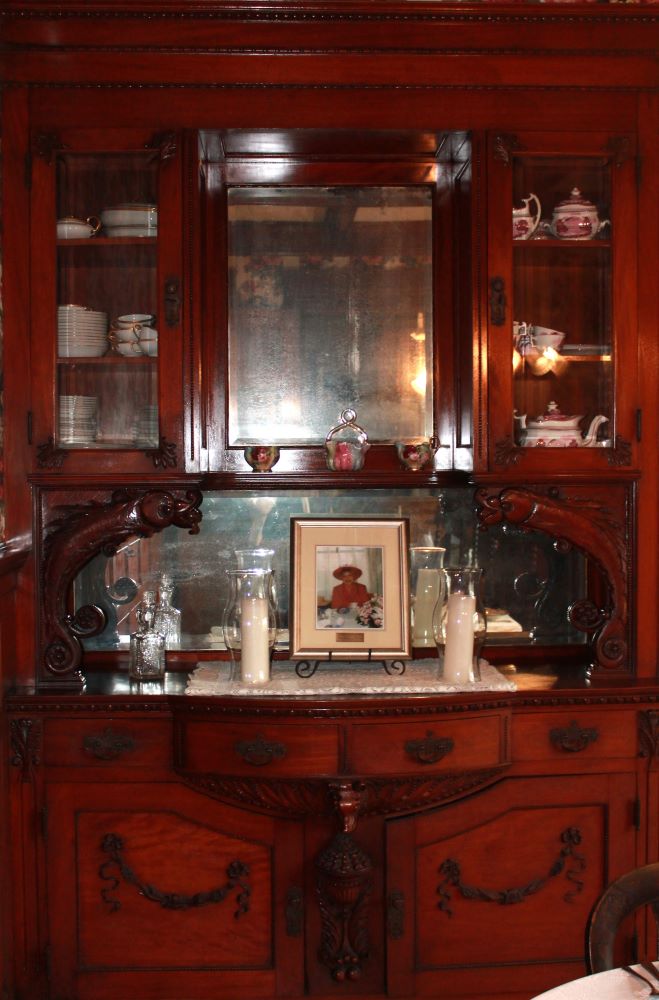

The breakfast room sideboard is truly the outlier of the Van Dykes’ expansion. It is not transitional or forward-thinking. Instead, it reflects the design taste of the middle 1800s. Sideboards were very common in Victorian homes; they were seen as a way to showcase the homeowner’s economic status and design style.[14] The dining room’s sideboard was there from the conception of the home. That one is very typical to the Victorian Shingle Style woodworking designs, just with a few flairs like double spandrels on the sides. The breakfast room sideboard has nature, food, and animal motifs, which seemed counter to the movement towards simplicity of the time. In the mid-1800s, these motifs were seen as an interesting dichotomy in the dining room. There were alive and dead animals which connoted hunting and feast-like bounties that represented cooked food.[15] There have been arguments in academia that this was about the duality of gender in the dining space: hunting for men and cooking for women. However, it is also the lifecycle of food, alive and growing to dead or harvested and prepared. Not to mention, again, being a nod to the prosperity of the household. This motif went out of style. Sarah Kelly wrote an article on sideboards for the Art Institute of Chicago and commented, “Prominent carvings of fruit, game, and seafood… mirrored the bounty of the owner’s table. Yet such decoration, with its connotations of hunting and violence, came to appear vulgar.”[16] Most sideboards created in the late 1800s and early 1900s would not have chosen this motif, so it is odd that the Van Dykes did. It could be the hypothesis that the center of the United States is always the slowest to adopt or abandon trends, or perhaps the Van Dykes liked that style, or it was the specialty of the artisans they hired. Whatever the reason may be, the breakfast room sideboard is the outlier of the Van Dyke expansion’s design.

The Van Dykes’ renovation to 632 W Market Street was the most extensive of all the owners of the home, almost doubling the square footage of the house. They added space and modernized while still mostly matching the design of the existing house. The Van Dykes’ home was a place for entertaining and living grandly, which we will talk about next month with an article on Emma Van Dyke.

[1] “The MacDonell House,” Allen County Reporter, 1994, M-7

[2] Patricia Smith, “John & Edna,” Allen County Reporter, Vol. LX, 2005, No. 1, 9,

[3] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” Allen County Reporter, Special Issue, Vol. LXVII, 2013, 11.

[4] Patricia Smith, A Detailed Resource Guide, 2012, 107

[5] Ibid., 161.

[6] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 11.

[7] Patricia Smith, A Detailed Resource Guide, 107

[8] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 15.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Patricia Smith, A Detailed Resource Guide, 161.

[11] Ibid., 195.

[12] Ibid., 128.

[13] Rist, Curtis. “Coffered Ceiling can add Extra Dimension to a Room.” Tapa Bay Times. September 28, 2005. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1999/02/27/coffered-ceiling-can-add-extra-dimension-to-a-room/.

[14] William, Susan. Savory Suppers and Fashionable Feasts: Dining in Victorian America. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1996. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BozSIXPcn-cC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=victorian+buffet&ots=nHWKBws3qg&sig=w708K4BEJCQXY59-YHCJzJd4X7s#v=onepage&q=victorian%20buffet&f=false67.

[15] Ibid., XVIII.

[16] Kelly, Sarah E. “Sideboard.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. Vol 31, No. 1, Notable Acquisitions at The Art Institute if Chicago (2006). Accessed March 12, 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4104487, 18.

Ernst, Mark, Darwin D. Martin House, 125 Jewet Parkway, Buffalo, Erie County, NY, Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0203/.

Kaminsky, David J., James Off House, Paradise Road, Smithville, Clay County, MO, Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/mo0370/.

Tilley, Laurence E., Sideboard in Dining Room, Library of Congress, accessed April 3, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ri0222.photos.145503p/.

Unknown Photographer, First Floor Dining Room, Detail of Sideboard, Library of Congress, accessed April 3, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/tx0541.photos.155214p/.

All other photos used are from the collection of the Allen County Museum.

Leave A Comment