Before we dive into the Hoover expansion, , it will be helpful to go over a few facts about the Van Dykes’ time at 632 W Market Street, aka the MacDonell House. Emma and John moved into the house in 1897, after exchanging houses with the Bantas.[1] They renovated it between 1900 and 1902, and then moved out in 1903/1904.[2] For a significant amount of time, the house would have no residences.[3] One might wonder why it took so long for John to sell the house? The simple answer is that John and Emma put too much money into 632 W. Market Street; somewhere around $20,000 is the estimate.[4] John B. Kerr was reported to have offered John $30,000 before the Van Dykes had even moved out, but John wanted $33,000.[5]

The house at 632 W. Market Street would be unoccupied for eleven years, with a single groundskeeper taking care of it during that time.[6] When the house was finally purchased in 1915, journalists called it “The House of Mystery” and claimed that ghosts walked around the upper floors.[7] Luckily, furniture store owners, William F. and Ida Hoover were not dissuaded by melodramatic newspaper articles. However, they were very keen on updating, modernizing, and making this long unoccupied structure a home for them and their two almost-adult daughters, Pallene and Allene. They purchased the house in the middle of July 1915, hired Lima architectural firm McLaughlin and Hulsken almost immediately, and began remodeling on August first of that year.[8] The Hoovers would go on to design the final significant, historic remodel of the MacDonell House.

The Allen County Museum has the work plan for the Hoovers’ redesign, in its collection. The museum does not have that information for the Van Dykes’ plan, and the blueprints are the only piece of evidence for the original Banta layout. The significance of the work plan and proposal is that it not only shows us much of what the Hoovers’ new renovations would be, but it also what changes had been made in the past. It must be noted that they did not end up doing everything on the plan. For example, the remodeling guide states that all the woodwork in the house was to be painted white.[9] This did not occur everywhere; and much of the beautiful, stained woodworking in the house was saved with only a few rooms painted white. We will never know exactly what happened, but we will choose to be grateful it is not all white.

The planning document, which is nine pages long and typewritten, mostly focuses on repairs or modernizations. There were also overall concerns for the whole house: making sure the windows worked; repairing or replacing hardwood floors; repairing window sashes; and fixing the electric wiring. Just note that almost all those things are being done on each floor as we go into specifics by floor; then, in the last paragraphs, we will discuss the major changes the Hoovers made during their renovation.

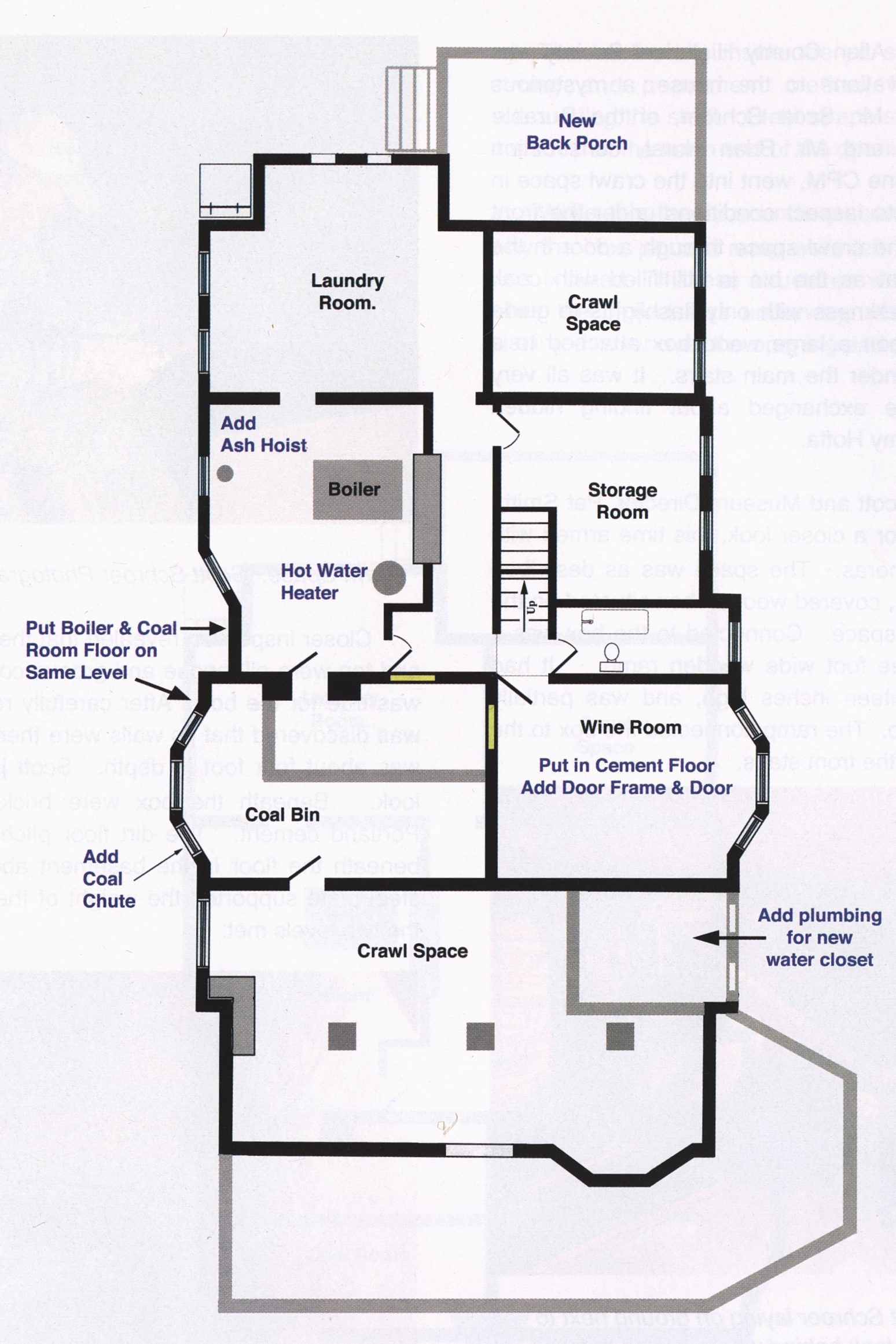

The basement is where we will begin. During the Van Dyke renovation, a bathroom and a laundry were added to this level.[10] After eleven years of disuse, these werein need of renovation. The reconstruction began with the entire basement floor torn up, and then, cement flooring was poured, the walls and ceilings were replastered, and floor drains were added to many of the rooms in the basement for drainage.[11] Likewise, as you can see in the layout, a wine room was added.[12] The basement is one of the places, in this renovation, that best illustrates how much innovation had happened in those eleven years—such as the water heater that was installed. The first automatic storage water heater was invented in 1889 by the Norwegian engineer Edwin Ruud.[13] As with most inventions, it took some time to work out the kinks before selling on the mass market. Thus, it was not common in houses of the time. In fact, later in 1920, only 1% of homes in the United States had indoor plumbing to utilize such a heater.[14] So, the Hoovers having one in 1915 was remarkable. Therefore, as we have seen numerous times, 632 W. Market Street was far ahead of the curve in modernization. The water heater and the furnace were coal-burning, so they added two other little luxuries. The first was a coal chute, a top-of-the-line Majestic brand coal shoot. Reportedly break-proof, burglar-proof, and rust-proof, a Majestic coal shoot was asked for by name in the plans and is still part of the house today.[15] Before this, it is believed that the coal had to be carried in and the ashes carried out by the back staircase of the basement. The Hoovers also meant to rectify the ash removal by adding an ash hoist in the boiler room, right next to the water heater and furnace.[16] So, the ash could be put in a bucket, hoisted to the window near the ceiling of the basement, and taken outside through that window with ease.[17] No doubt, the Hoovers themselves did not use this; however, the domestic servants probably loved these modern luxuries. Thus, the basement was once again modernized and wholly livable for the Hoovers and their domestic servants.

The main floor had the least number of changes other than general repairs and aesthetic tweaks. The hardwood flooring in the parlor and library may not be the most striking change, but they are significantly different from the previous owners’ flooring. Area rugs cover most of the flooring in both rooms today; however, unlike the rest of the flooring on this level, neither room has parquet flooring. They most likely did before the Hoover renovation, but these floors were specifically pointed out in the project plan as needing to be redone.[18] Now, they have skinny boards with lots of nails and no design. Another adjustment that was made to the house was extending the back porch off the kitchen facing north. This extension was done expressly to make room for the sleeping porch above it, which we will discuss when we get to the second floor. The last significant change to the main floor was the addition of another bathroom on that level. Before this article was finished being researched, there was some confusion by its writer’s part about the main level powder room. It was known that the Hoovers added a powder room to the main floor; incorrectly, this writer thought this was when the powder room by the kitchen was added. Instead, it was added during the Van Dyke expansion. The Hoovers added another small bathroom under the main staircase.[19] The door beside the staircase leads down a few stairs to a small room, which had a bathroom “stall” off to the right and a sink outside the “stall.” This brought the Hoovers’ number of bathrooms up to two on the main floor.

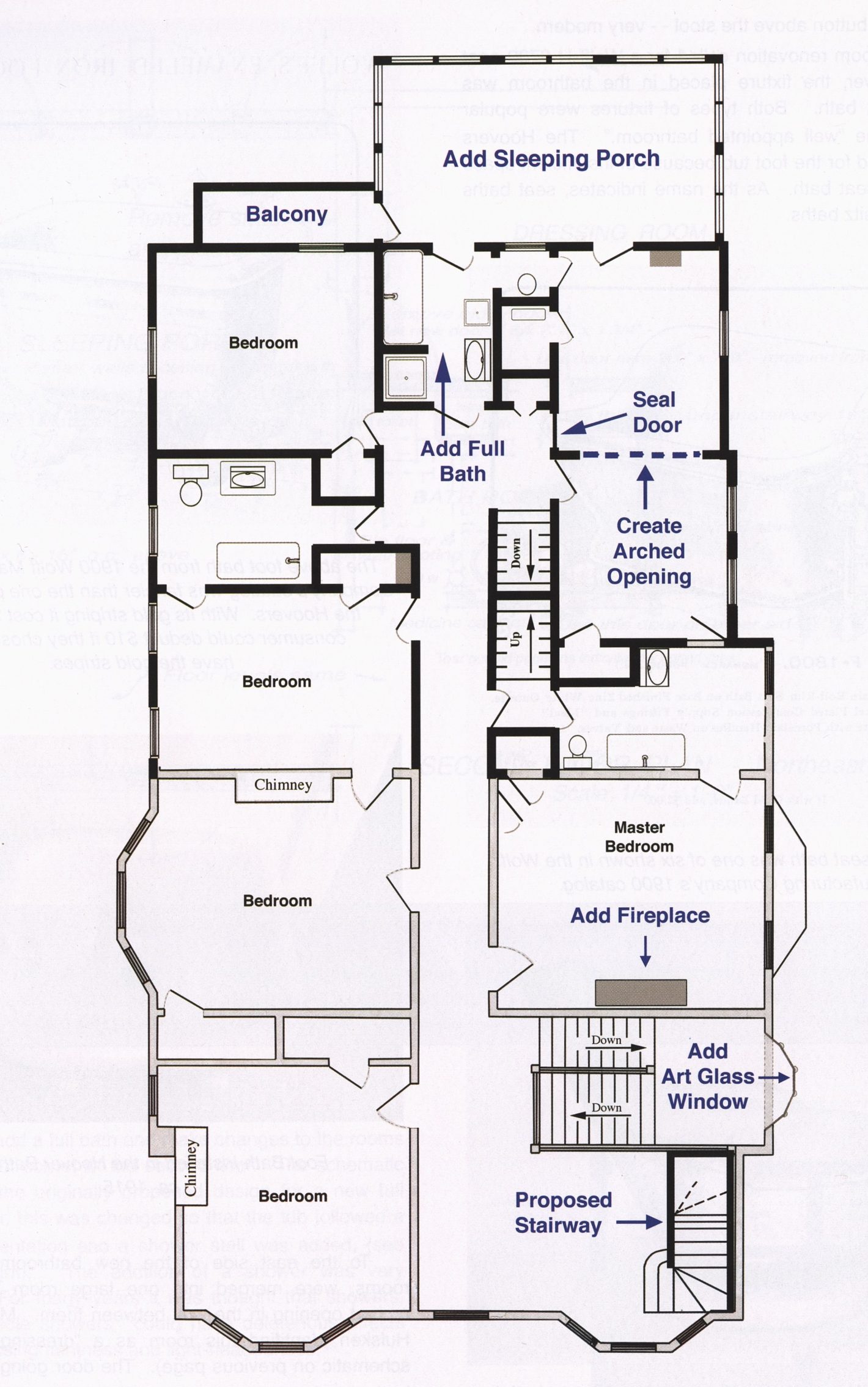

The second and third floors also had a few smaller-scale changes conducted during the renovation. Almost every room on this floor is noted as having a carpet that was removed for new hardwood flooring.[20] Thus, again, we lost some of the parquet flooring. The early 1900s use of the word carpet is different from our use today; most likely, carpet referred to something that was more like what we would call a rug, and nothing that was tacked down to the floor.[21] During the revamp, there was also special consideration given to the west bathroom, which is better known as the marble bathroom. The Hoovers wanted all the marble cleaned up and for the bathroom to be usable once more. No doubt, the bathroom is one of the most show-stopping rooms in the house. Likewise, it could have been the bathroom that Pallene and Allene shared while living in the house, so it needed to be functioning. Another change on this floor was combining the two northeastern bedrooms. The wall between them was demolished as well as one of the doorways to make it one large space. We do not know the function of this new larger space in the Hoovers’ lives. However, it seems likely that with the new bathroom position and sleeping porch, both to be discussed next, the room no longer made sense as a bedroom. An oral history informs us of one of the other changes on the second floor—the main bedroom’s fireplace. According to the story, Ida Hoover loved the design of the southwestern bedroom’s fireplace. William found her a very similar fireplace, however, there was no chimney in the primary bedroom. Thus, the fireplace front and mantel are only for the aesthetic and are not usable as a fireplace. Very little was done to the third floor of the house. Unlike the Van Dykes, the Hoovers were not known for throwing parties. Nevertheless, with the addition of the sleeping porch, they decided to add a balcony on top. This could be accessed from the northeastern servant’s room. It seems like an odd place to put a balcony, but it was logical in the sense that they could easily get to the roof of the sleeping porch for repairs. Again, we see that the Hoovers’ redesign was focused on functionality, with a bit of fun and modernity thrown in.

The Hoovers made three major design choices when they bought and renovated 632 W Market Street. The first and most obvious for anyone looking at the house is the addition of the sleeping porch on the northeastern side of the second floor. As mentioned above, this addition covered the back porch and added a balcony to the third floor, therefore visually changing the house’s exterior significantly. Before air-conditioning was invented, sleeping porches were usually added to houses to create a cooler place to sleep.[22] There were also health movements at this time focused on spending more time outdoors.[23] Perhaps the Hoovers were interested in spending more time outdoors. Although, having a cool place to sleep was most likely the primary goal of the addition. Now, with its light, airy feeling, and all the windows, it’s a favorite room in the MacDonell House among staff and visitors. The porch also has radiators, so it could have been used throughout most of the year, making it an even more practical space.[24] With this sleeping porch addition, the builders also added on a balcony right to the left of the room. It is very small and thin, but it gives an unsheltered place to be outside on the second floor. This is the largest of the major renovations from the Hoover era and one of the most beloved.

Right next to the sleeping porch was the location of one of the Van Dykes’ second-level bathrooms. We might remember from that expansions article, read here, that there was this odd little room shown as just a toilet in a closet.[25] Well, it seems the Hoovers did not want just a toilet in a closet, or even a powder room if that was the original design. They wanted an ultra-modern bathroom. So, their plan removed the back hallway and the hall closet to make a full bathroom. The most important thing to note about this renovation was the addition of a shower. This was one of the first showers to be built into a home in Lima. In the United States, showers would not become popular for another decade for those who would not be considered wealthy.[26] There is also a large bath and a foot bath in the room. The foot bath is believed to have been added because there was not enough room for a seated bath, but the Hoovers still desired a place to bathe themselves quickly. The other unique aspect of the bathroom is the little toilet room, which is so tiny that the tank for the toilet is in the adjoining closet. The toilet room is accessible through the now larger northeastern bedroom and the bathroom. That area, of the home, becomes almost a maze of doors with the sleeping porch, hallway, bathroom, and northeastern bedroom. However, it all is worthwhile for the luxuries of a shower, foot bath, and sleeping porch.

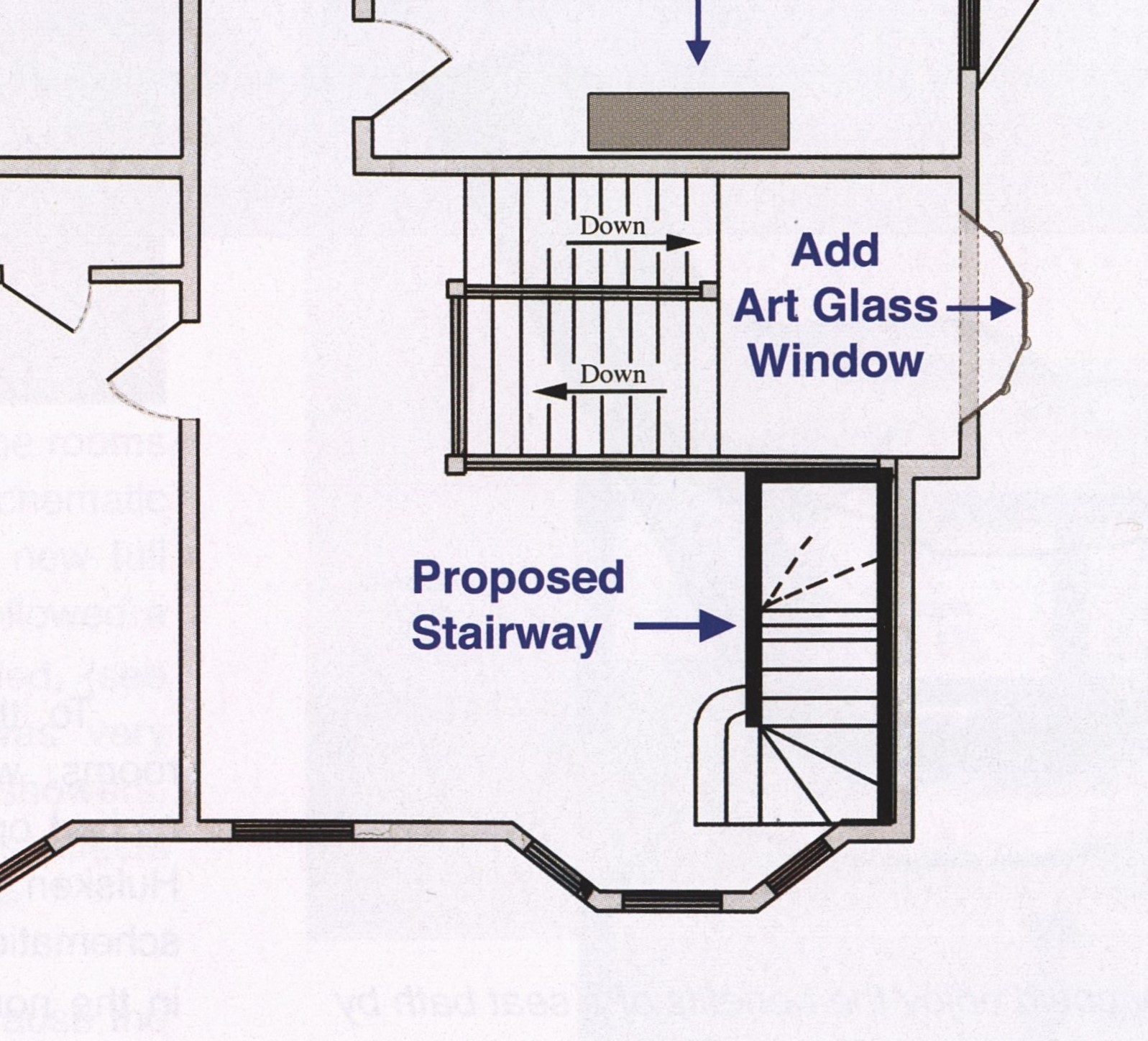

The last major renovation the Hoovers did in the house was the stained-glass windows that grace the main staircase. Since the stained-glass was not ]in the original design of the house, , it almost feels as though the house was incomplete before this addition. However, as part of the plans for the remodel, the “new art glass window glass” was placed into the bay window on the staircase landing.[26] The design of the stained-glass was very contemporary to the times, inspired in coloring and subject to the Arts and Crafts movement and Tiffany Glass. Unfortunately, the window is not signed, and there are no maker’s marks anywhere on the windows, so we have no definitive creator or designer. It is one of the home’s highlights, especially since it was restored last year. There was one other thing planned near the main staircase— a set of stairs on the east wall of the music room to give another entrance to the third floor. Unfortunately, this was never completed. We should all mourn this because, with two entrances/exits, the third floor could have been visited by the general public.

The Hoover expansion of 632 W. Market Street added many beloved additions to the house and modernized it in many ways past 1915. They bought a beautiful home that had been unoccupied for eleven years to restore and upgrade it, from the new water heater in the basement to installing one of the first residential showers in Allen County. The stained-glass window and sleeping porch were both added by the Hoovers and are marquee parts of the home that visitors remember. Overall, the Hoover family buying the home saved it from falling into utter disrepair and perhaps even being utterly forgotten after John Van Dyke passed. The Hoovers and the other three families who lived there made it into the building we love to visit today.

[1] The MacDonell House,” Allen County Reporter, 1994, M-7.

[2] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” Allen County Reporter, Special Issue, Vol. LXVII, 2013, 11.

[3] An Unknow Article from Lima Republican Gazette, Held in the MacDonell House Research Material.

[4] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 26.

[5] “Van Dyke Mansion Long Untenanted Has New Owner,” The Lima Republican Gazette, July 18, 1915, Held in the J. W. Van Dyke Files in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Editor on Slope,” The Lima Daily, July 22, 1915, Held in the J. W. Van Dyke Files in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[8] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 26, and An Unknown Article in The Lima Daily News, July 19, 1915, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8017/images/NEWS-OH-LI_DA_NE.1915_07_19_0002.

[9] “Remodeling of the Van Dyke Residence for Mr. William Hoover, Lima, Ohio,” Held in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[10] Patricia Smith, A Detailed Resource Guide, 107.

[11] “Remodeling of the Van Duke Residence for Mr. William Hoover, Lima, Ohio,” Held in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 34.

[14] Carol McGarry, “How Americans Got into Hot Water,” October 4, 2019, Accessed June 6, 024, https://blog.sense.com/how-americans-got-into-hot-water/.

[15] Ad for Majestic Coal Window, A Detailed Resource Guide, 210.

[16] “Remodeling of the Van Duke Residence for Mr. William Hoover, Lima, Ohio,” Held in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 33.

[20] “Remodeling of the Van Duke Residence for Mr. William Hoover, Lima, Ohio,” Held in the Allen County Museum Archives.

[21] Murray L. Eiland, “Rug and Carpet,” May 13, 2022, Accessed June 6, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/technology/rug-and-carpet.

[22] Patricia Smith, “Within These Walls: An Investigation into the Early Years of the Mansion Next Door,” 27.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Patricia Smith, A Detailed Resource Guide, 161.

[26] “A Brief History of the Shower,” April 16, 2014, Accessed June 6, 2024, https://www.showerdoc.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-the-shower.

[27] Ibid.

All photographs included were either taken by an ACM employee or from the ACM Archives

Leave A Comment